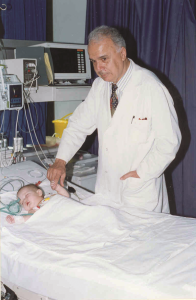

“I am truly happy to have chosen the field of medicine and to have found, during my professional life of almost 50 years, the chance to successfully perform numerous surgical operations never done before in my country and the world.

No doubt I have made all effort to approach all my patients with the same sense of responsibility, concern, care and compassion in the more than 12,000 surgeries I have performed.

However, the successful results of surgeries I performed on children and babies, particularly on one-day-old babies have always held an extremely special meaning for me.

With a surgery on adults, you can perhaps add ten to fifteen years to their lives.

With a surgery on adults, you can perhaps add ten to fifteen years to their lives.

But can you imagine the joy of adding hopefully 70 to 80 years to the lives of young babies of 7 to 11 pounds, on their first day in the world, as you complete their surgeries after opening that tiny walnut-size heart and putting on those extremely thin, delicate veins the stitches of half a millimeter, only visible to the head assistant closest to you, which won’t allow for the slightest misstep.

Their hearts always live in mine…”

![]()

The Early Years…

I was born in Istanbul on April 23rd in 1931.

At the time my father, Şevket Süreyya Aytaç, was Director of Education in Istanbul, and my mother, Cemile Aytaç, was Vice-Principal and  Teacher of Turkish Literature at Istanbul Girls’ High School.

Teacher of Turkish Literature at Istanbul Girls’ High School.

When I reached elementary school age, my parents were appointed to new positions in Ankara. Hence, I finished elementary school in 1942 at TED Ankara Koleji; secondary school in 1945 at Ankara 3rd Orta School; and high school in 1948 at Ankara Atatürk Lisesi. I was at the top of my English class every year all through high school, while Nihat Özsan, a close friend of mine since secondary school, graduated at the top of his German class.

When I reached elementary school age, my parents were appointed to new positions in Ankara. Hence, I finished elementary school in 1942 at TED Ankara Koleji; secondary school in 1945 at Ankara 3rd Orta School; and high school in 1948 at Ankara Atatürk Lisesi. I was at the top of my English class every year all through high school, while Nihat Özsan, a close friend of mine since secondary school, graduated at the top of his German class.

←(Watercolor portrait of myself, painted in 1940 by Nusret Karaca, a distinguished artist who was a friend of my parents.)

My mother wanted me to attend Istanbul University like Nihat, and get a Master of Science degree from the Faculty of Engineering. However, I had the Faculty of Medicine on my mind.

My mother expressed her concerns, saying, “My dear Aydın, you are so tender-hearted, you will be burdened and distressed by the troubles of all those patients. Please, do give up this dream and become an engineer instead.” I cared deeply for my mother and I obeyed her wish.

There were 20,000 applications for the Faculty of Engineering and a total of 360 students were placed in four departments. We were a remarkably successful group of 42 students in my high school class. Twelve from the group were among these 360 students, while Nihat and I were among the top 60 students selected for the master’s program in engineering. It was an excellent school offering high quality education and attractive job opportunities after graduation.

In Istanbul, we rented a room in Nihat’s grandmother’s house. The grandmother lived in a small room upstairs, while Nihat and I had a room downstairs with a bathroom and a kitchen. We used to walk to the university in the morning and walk back in the evening. Everything seemed to be fine, but I still had medical school on my mind. Around that time we had read in the papers that the King of England was going to have an operation. One night in my dream, I saw myself performing lung cancer surgery on the king for many hours. When I woke up I remembered the entire dream and felt in my heart an unquestionable desire to go to medical school. I shared my feelings with my friends and said: “When I go home at the end of the semester, I’ll talk to my parents. I’ll ask my mother’s consent and give up engineering to enter medical school next year.”

At the end of the first semester I went home to Ankara and told my parents that I truly wanted to transfer to the Faculty of Medicine at Istanbul University.

“My dear Aydın,” said my mother, “you’d better continue in engineering until the end of the year, you can then reconsider your decision.” She was no doubt hoping that if I stayed there for a year, I would perhaps warm up to engineering and continue my studies in that field.

I wanted to convince her without causing any hard feelings, so I sat by her side and spoke gently. “My dear mother, I can become a good engineer if you want me to,” I said, “but if you permit me to become a doctor, I’m sure I will achieve much greater success than as an engineer.” My father also supported me by saying, “Even as a child, we treated Aydın as a grown-up and he has always made very rational decisions. Since he wants to go to medical school, let’s not force him any more to stay in engineering. He can leave the school now and we might get some help to send him to Europe to improve his English before he goes to medical school.”

But only two days after this conversation, my father came home early in the evening and said: “My dear Aydın, the Faculty of Medicine at Istanbul University has just announced their decision to take in an additional group of sixty students in mid-winter.” They had already accepted 600 students at the beginning of the year. Now, as the candidates had to apply within two days, my father said, “If you wish, you can go to Istanbul by the 8 o’clock train this evening.”

I was so overjoyed that I thanked my father profusely and hugged my mother several times to comfort and cheer her up.

I was so overjoyed that I thanked my father profusely and hugged my mother several times to comfort and cheer her up.

(My mother Cemile Aytaç (1909-2007))→

←(My father Şevket Süreyya Aytaç (1889-1972))

I went to the central station to get a ticket, but there were no seats left on the train. I explained my situation to the person in charge: “If I can’t take the train to Istanbul tonight, I might lose my chance to enter medical school.” The man said: “I’ll give you a ticket right away, young man, but there are no seats available. You are young and healthy; you can stand in the hallway during the trip.” I thanked him and bought the ticket. I spent the whole night standing in the hallway for twelve hours. Only after six o’clock in the morning, when the passengers in the wagon went to the lavatory, I could sit down and get some rest for about ten minutes.

The next morning I took immediate action for registration. First I went to the Faculty of Engineering to request the documents which I needed for my transfer to the Faculty of Medicine. They told me that I had easily entered this school despite quite challenging requirements. They were pleased with my performance and believed that it would be for the best of both sides if I stayed there. But my decision was final. I said, “I definitely want to go to medical school and do my best to serve my country as a doctor,” and took my documents.

Although I started in mid-winter, I completed my courses within five years and four months and graduated in 1955 together with the students who had started three or four months earlier than I did. I can never forget the extent of my father’s sacrifice. There was a medical school in Ankara as well, and if I had attended that school I could go on living in our home there. Instead, my father rented a house in Istanbul and supported me for five and a half years, which I believed was a major sacrifice.

When I was in my senior year at the university, there was an outstanding German-Jewish professor among my teachers. Dr. Frank was one of the distinguished academics who, thanks to Atatürk,  had made great contributions to higher education in our country. He was a professor of internal medicine and cardiology. He used to teach three times a week, and doctors as well as students came to his classes to hear his lectures. He would present a case at each class period and describe it in detail.

had made great contributions to higher education in our country. He was a professor of internal medicine and cardiology. He used to teach three times a week, and doctors as well as students came to his classes to hear his lectures. He would present a case at each class period and describe it in detail.

←(My years at İstanbul Faculty of Medicine. We are at the anatomy class and I am the second from the right.)

One day he had brought an eleven year old girl to the class. He made his diagnosis and after he sent the girl away, he said: “My diagnosis is PDA (Patent Ductus Arterious). Unfortunately we cannot cure this child because this particular surgery is not yet performed in Turkey. However, three months from now a professor from Belgium, who is a heart surgeon, will be visiting and if he consents, the surgery will be performed.”

When I came out of class that day, I made a resolution: “I will learn about all types of heart surgeries in the U.S. and come back to my country right away.” It was an operation performed in the U.S. back in 1938 and it still couldn’t be done in Turkey in 1954, when I was a senior at the university. It was a simple surgery which a well-trained surgeon could perform with the help of an assistant.

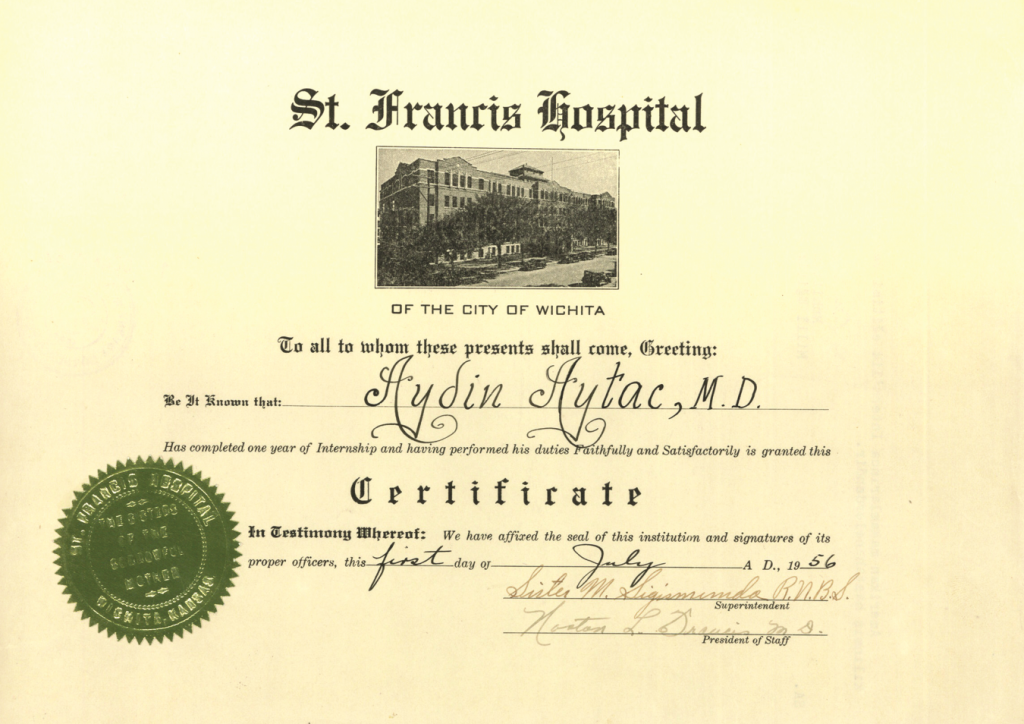

In my senior year, toward the end of my happy and successful days at Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, I applied for residency programs in the U.S. The system called ECPMG compared the preferences of the applicants with the ten hospitals that voted for them. If there was a match between your preference and the vote of that particular hospital, it meant you succeeded in attaining your goal. About three months later, I received a reply saying St. Francis Hospital in Wichita Kansas had voted favorably for me and my preference matched their vote. I decided to go there for the general surgery program, which was a prerequisite for the heart surgery residency program.

I received a reply saying St. Francis Hospital in Wichita Kansas had voted favorably for me and my preference matched their vote. I decided to go there for the general surgery program, which was a prerequisite for the heart surgery residency program.

←(We are at the meeting of the Graduation Ball Committee and I am sitting in the middle.)

In those days you had to go into military service the year after your graduation and it was not possible to go abroad before completing your service. I was not going to the U.S. that year, so I had five or six months before me. If I graduated that year, I would have to join the army in the coming year. Therefore, I postponed taking one simple course to the new year. I came back on January 6 to take the exam, successfully passed it and graduated. I did my military service in a military hospital in Ankara after I returned from the U.S. As a matter of fact, my service covered a period of two-and-a-half years.

At the time I left for the U.S., my wife Şükran and I had been married for three months. We set out on our journey one month before I started my general surgery residency. We traveled on a ship for the double purpose of enjoying a vacation and improving my English.

(My wife Şükran Aytaç)

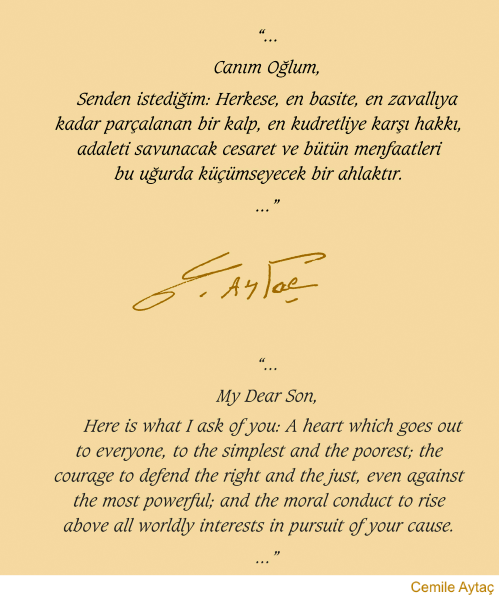

Even though my dear mother had once wanted me to become an engineer, I knew that I had finally made her happy by successfully completing my education in medical school. Before I left Turkey to start the residency programs in both general and cardiac surgery, my mother had secretly written the following lines in my notebook:

“To My Son,

You know that you and you sister are the light in my heart, the sparkle in my eyes, and the essence of all my life. Your outstanding intelligence and the way you lived for 24 years have filled me with enough pride to make my head reach up and touch the sky.

As I look at you, I remember the days when I was miserable about so many dreams we were unable to fulfill. Now I see that they have left my heart and your father’s to take shelter in your youthful being and are meant to blossom in your hands. I believe with all my heart that my young sapling will sooner or later give them color and fragrance. You certainly know the principles guiding our life and we are fortunate that you can find the best examples there. You also know that a misguided act will make us more miserable than anything or anyone else can.

I cannot ask you to conduct your life in a certain way. The fine atmosphere of our home has already woven all my wishes into your soul and brain with golden rays. I expect from you great ideals and extraordinary success.

My Dear Son,

Here is what I ask of you: A heart which goes out to everyone, to the simplest and the poorest; the courage to defend the right and the just, even against the most powerful; and the moral conduct to rise above all worldly interests in pursuit of your cause.

A philosopher once said, “To exist is to share yourself.”

I want my son to grow and reproduce and fill the universe with his achievements everywhere and for everyone.

Another philosopher defines happiness as something “given to others and received from them”.

Try to find happiness always by making others happy.

I trust you. I believe in you. I pray to God not to take away from me this trust and faith. Otherwise, just like a building without support, my collapse would be pathetic and disastrous.

Your mother (1955)

![]()

U.S. Years

After my departure, I opened my mother’s letter and read it. With a sense of joy and resolution inspired by those encouraging words, I started the general surgery residency program at St. Francis Hospital in Wichita.

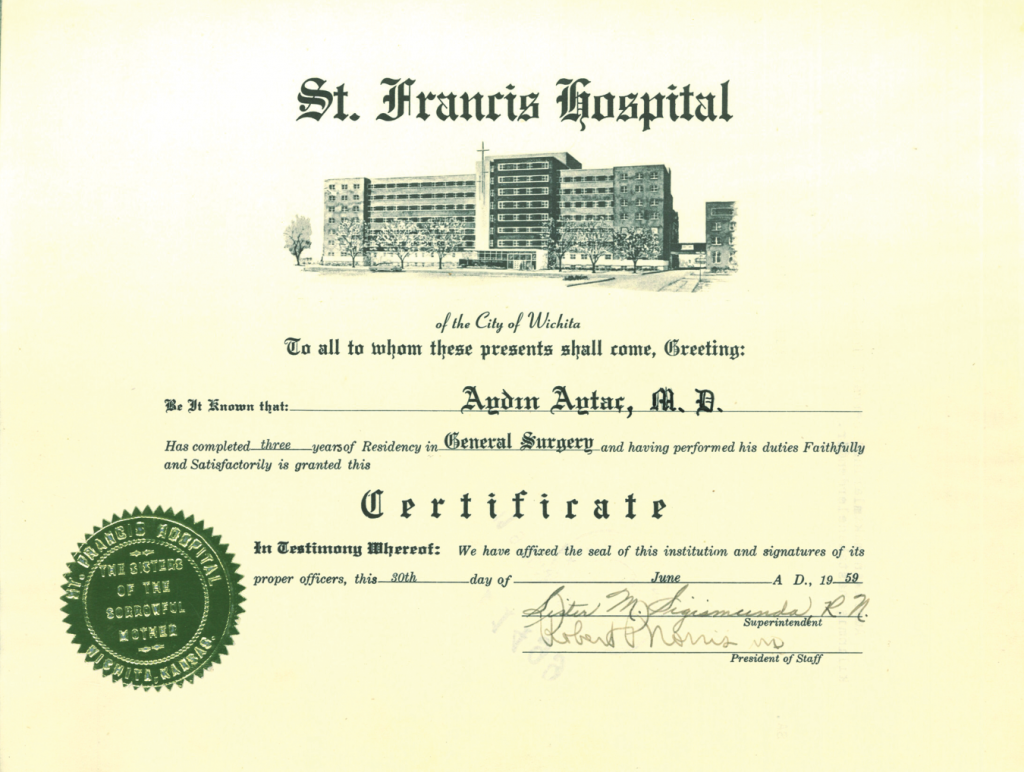

(St. Francis Hospital in Wichita-Kansas, where I did my general surgery residency.)

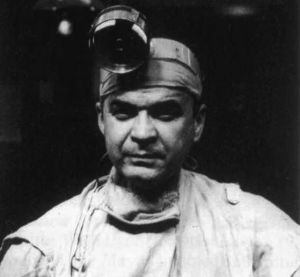

While I worked there as a resident doctor, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Professor Clarence Walton Lillehei and several other distinguished surgeons in the field of cardiovascular surgery.

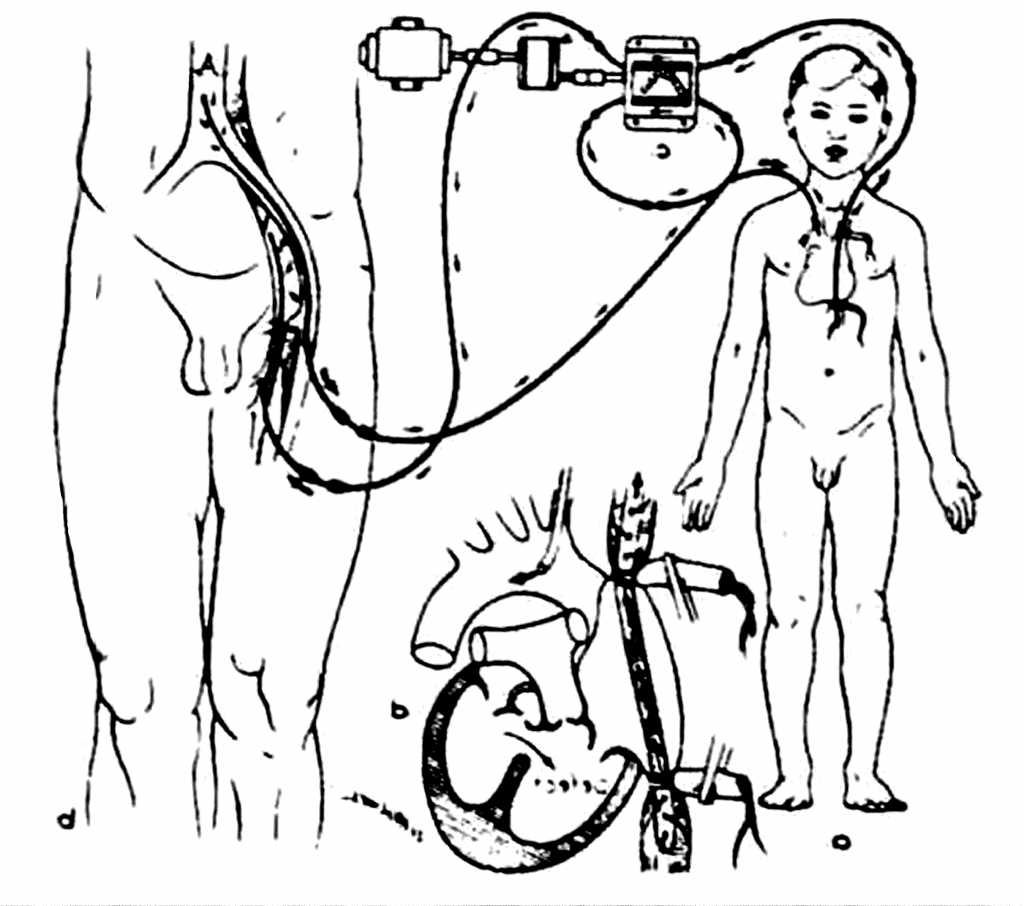

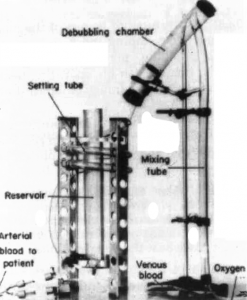

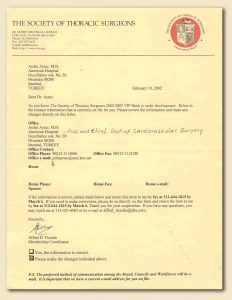

Dr. Lillehei had quite successfully performed his first eight heart surgeries in 1954, and six patients had survived. As seen in the diagram, instead of the artificial heart-lung machine, the patient’s mother or father was used in a cross circulation system. Lillehei published these eight cases in 1955, which was recognized as the beginning of a series of modern open heart surgeries.

(Clarence Walton Lillehei (1918-1999))→

(Prior to 1953, instead of the artifical heart-lung machine, the patient’s mother or father was used for cross circulation.)

The first open heart surgery with a heart-lung machine was performed by Dr. John Heysham Gibbon in 1953. The first patient survived but unfortunately all of the following four simple surgeries resulted in the loss of the patients. The surgeon then stopped performing these operations. In 1955,  Dr. John Kirklin called him to ask for the heart-lung machine and Dr. Gibbon sent it to him. Kirklin made some changes in the machine and successfully performed his first surgery in 1955.

Dr. John Kirklin called him to ask for the heart-lung machine and Dr. Gibbon sent it to him. Kirklin made some changes in the machine and successfully performed his first surgery in 1955.  He then continued to do heart surgeries at Mayo Clinic using the artificial heart-lung machine.

He then continued to do heart surgeries at Mayo Clinic using the artificial heart-lung machine.

(John Heysham Gibbon (1903-1973))→

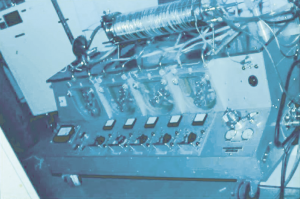

←(The 1955 version of the artifical heart-lung machine.)

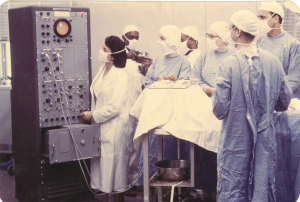

As of 1955, Lillehei also began to perform surgeries using the first artificial heart-lung machine, shown in the diagram, instead of using the parents. We watched artificial heart-lung machine surgeries performed on dogs in Minnesota in 1956 and began to use this equipment.

Dr. John G. Shellito, who was about fifteen years older than me, had worked at Mayo Clinic for a long time. In Minnesota, Lillehei had started performing heart surgeries. John G. Shellito had been elected president by the Midwest Medical Research Foundation in 1956 to set up the dog laboratory there. The three surgeons who had undertaken this project found an anesthetist assistant as well. They also needed a general surgery assistant to take on the entire task. We were six assistants there; five of them were Americans and I was the only foreigner.

One evening John Shellito called me at my home. “Aydın, surgeries have been started at two locations in the U.S.,” he said. “As you know, I worked with John Kirklin at Mayo Clinic. We performed general surgical operations and lung surgeries without a machine, and much less frequently, we performed heart surgeries. Now, with the support of the Midwest Medical Research Foundation, we are setting up a laboratory.” Shellito added that in order to gain sufficient experience, they would start doing surgeries on dogs, using the artificial heart-lung machine. They had three heart surgeons and they also needed a general surgery assistant. “Among the six assistants, you are the one most interested in heart surgery,” he said, therefore I make the first offer to you. Between 7:30 AM and 7:30 PM on Saturdays or Sundays, we will be performing surgeries on dogs, using the artificial heart-lung machine. If you accept the offer, you will be working without compensation.”

and much less frequently, we performed heart surgeries. Now, with the support of the Midwest Medical Research Foundation, we are setting up a laboratory.” Shellito added that in order to gain sufficient experience, they would start doing surgeries on dogs, using the artificial heart-lung machine. They had three heart surgeons and they also needed a general surgery assistant. “Among the six assistants, you are the one most interested in heart surgery,” he said, therefore I make the first offer to you. Between 7:30 AM and 7:30 PM on Saturdays or Sundays, we will be performing surgeries on dogs, using the artificial heart-lung machine. If you accept the offer, you will be working without compensation.”

(John Gardiner Shellito (1918-2009))→

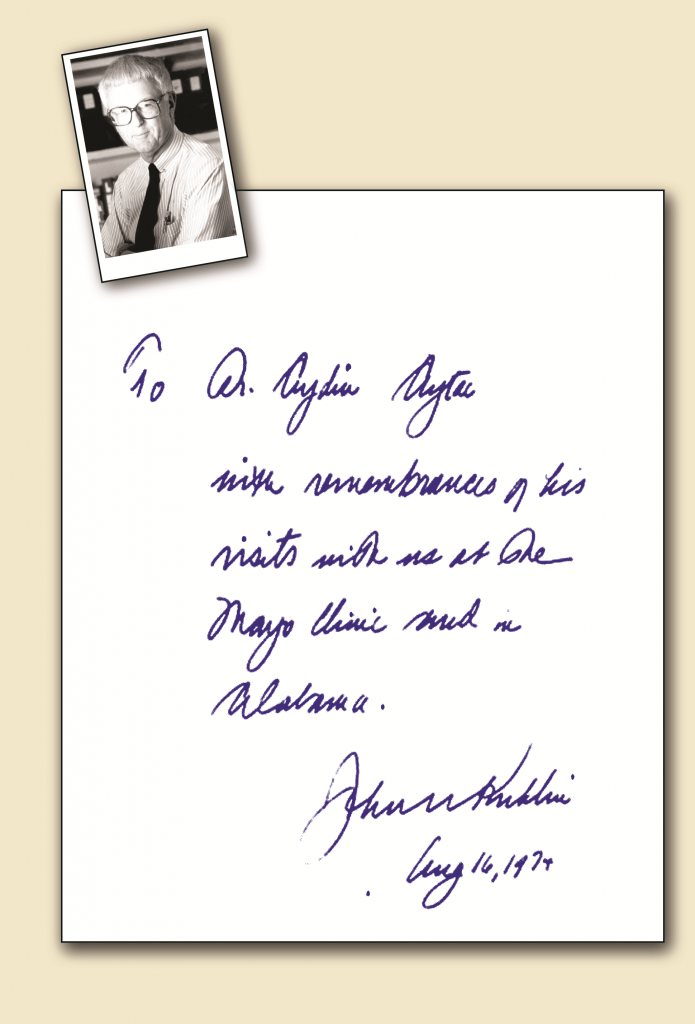

I accepted the offer right away. Every six months, one week would be spent in Minneapolis and one week at Mayo Clinic. This meant an opportunity to make on-the-spot observations of the methods, which were first used in these centers. In Minneapolis, where Dr. Lillehei worked, there was a proper dog lab.  We went there, stayed for a week and watched the surgeries on dogs every day.

We went there, stayed for a week and watched the surgeries on dogs every day.

←(Surgical Operations on dogs in Dr. Lillehei’s laboratory in Minneapolis.)

I had known Lillehei by name, but I saw him for the first time in this dog surgery lab. There was a surgical scar about 8 inches long on his neck. Dr Shellito introduced me to him and later told me that Lillehei had undergone a very serious surgical operation because of a malignant lymphoma in his neck.

Before the surgery Lillehei had said the following to the surgeon: “Do the operation in such a way that at the end there should be nothing left of the tumor or myself. In other words, don’t hesitate to remove the tumor completely; you can risk my life to the very end. But if a highly risky condition comes up after the surgery, don’t come and tell me you could not remove the tumor completely so as not to risk my life.” The young surgeon, with the courage and confidence prompted by this instruction, had not hesitated to perform the most radical surgery. With the excellent operation, the surgeon had saved not only Lillehei’s life, but also the open heart surgeries that were Lillehei’s contribution to humanity.

In Minneapolis, if there was an operation in the morning, I would watch Lillehei. We saw one heart surgery performed on a human, and another at Mayo Clinic. Then we came back, set up our lab, and started working as a team of six on Saturdays or Sundays.

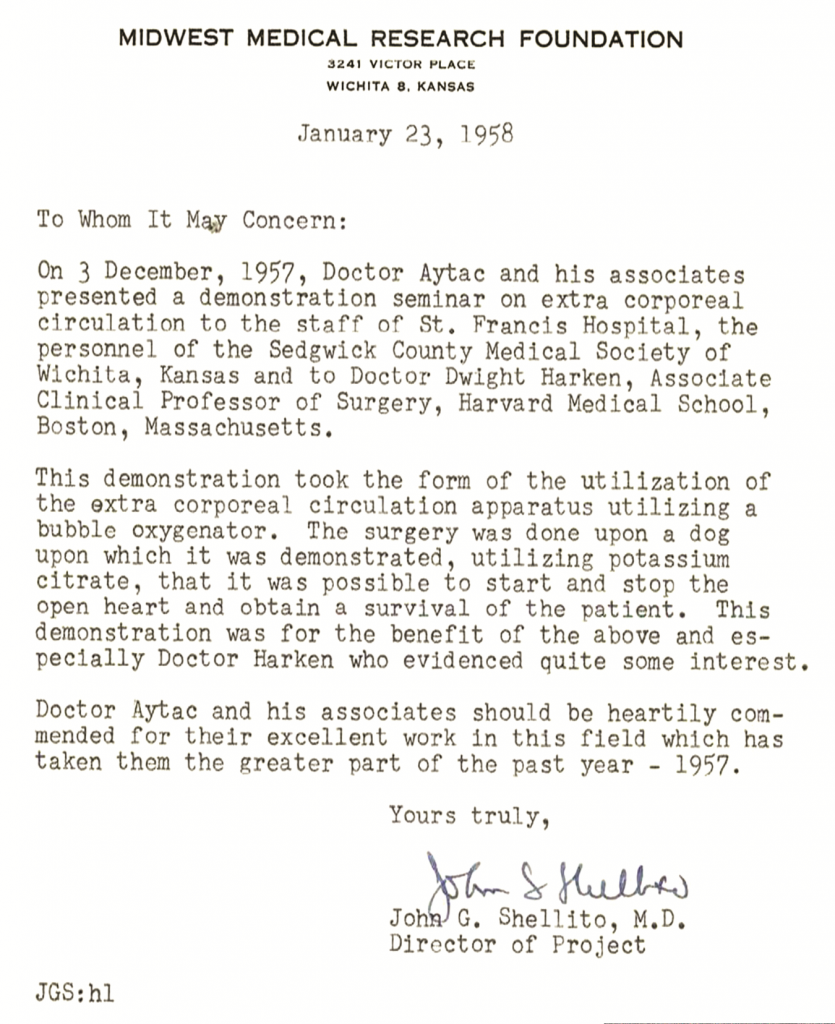

After a year and a half, one night in 1957, John Shellito called me at my home. “Aydın,” he said, “Dwight Harken, one of the best known heart surgeons in the U.S., will be coming here to give a lecture at 8:00 PM tomorrow. He has heard that we have been doing remarkable surgeries on dogs and he wants to see a surgery on a dog with a heart-lung machine before the lecture at 2:00 p.m.,” Shellito continued with an assertion and a question: “Aydın, you have the experience, you have to do this surgery. Can you do this tomorrow? We won’t be able to come.”

(In the dog laboratory of St. Francis Hospital.

Left to right: Perfusionist Gulliermo, Dr. E. P. Carreau, Dr. B. N. Buck, Dr. John Shellito, me and anesthesiologist R. H. Robinson)

I replied, “I can certainly do it and I will find an assistant to help me and he doesn’t even have to be a heart surgeon.”

Dwight Harken arrived at two o’clock. I performed the surgery using the artificial heart-lung machine. I stopped the heart and opened it. I went through the necessary steps, closed the heart, and then restarted it. Dwight Harken was very pleased. In the evening, as he began his lecture attended by all the heart surgeons in the city, he said: “I am very pleased to have witnessed here today an excellent dog surgery with an artificial heart-lung machine. I would like to express my appreciation and congratulations.” Subsequent to Harken’s praise of the successful artificial heart-lung surgery I did, Dr. John Shellito sent me a very nice letter of congratulations and thanks.

(The letter of congratulation and thanks sent to me by John Shellito upon Dwight Harken’s watching and praising the operation I performed.)

3 years later in 1960, Dwight Harken performed the first aorta valve surgery using an artificial heart-lung machine.

John Shellito and I presented our artificial heart-lung machine system and won an award in Topeka, a city known as the capital of Kansas, a couple of hours from Wichita.

(In 1957, when John Shellito and I were in Topeka.)→

In 1959, as we continued to perform the surgeries on dogs, one evening John Shellito called me at home. “Aydın, we have been very successful in dog surgeries. Now we will start surgeries on humans,” he said. “Tomorrow I’ll arrange for you to meet a child patient. Let’s perform an artificial heart-lung surgery on this child. I want you to do the operation.” I answered that I hadn’t yet finished my formal heart surgery residency and was not legally authorized to perform this surgery. “If anything happens to the child, I will be doomed, I will be convicted,” I said.

“How many dog surgeries did we do?” he then asked.

“156”

“How many of these did you do?”

“98”

“You, as one person, did 98 surgeries. We, three surgeons, did the rest. If you do the division, you’ll see we each did about 15 to 20 surgeries. Plus, you helped us in all of those operations. Don’t worry, if something goes wrong, the entire responsibility is mine. I will help as the first assistant and Dr. Buck will be the second.” Then I said, “OK, I will do it.”

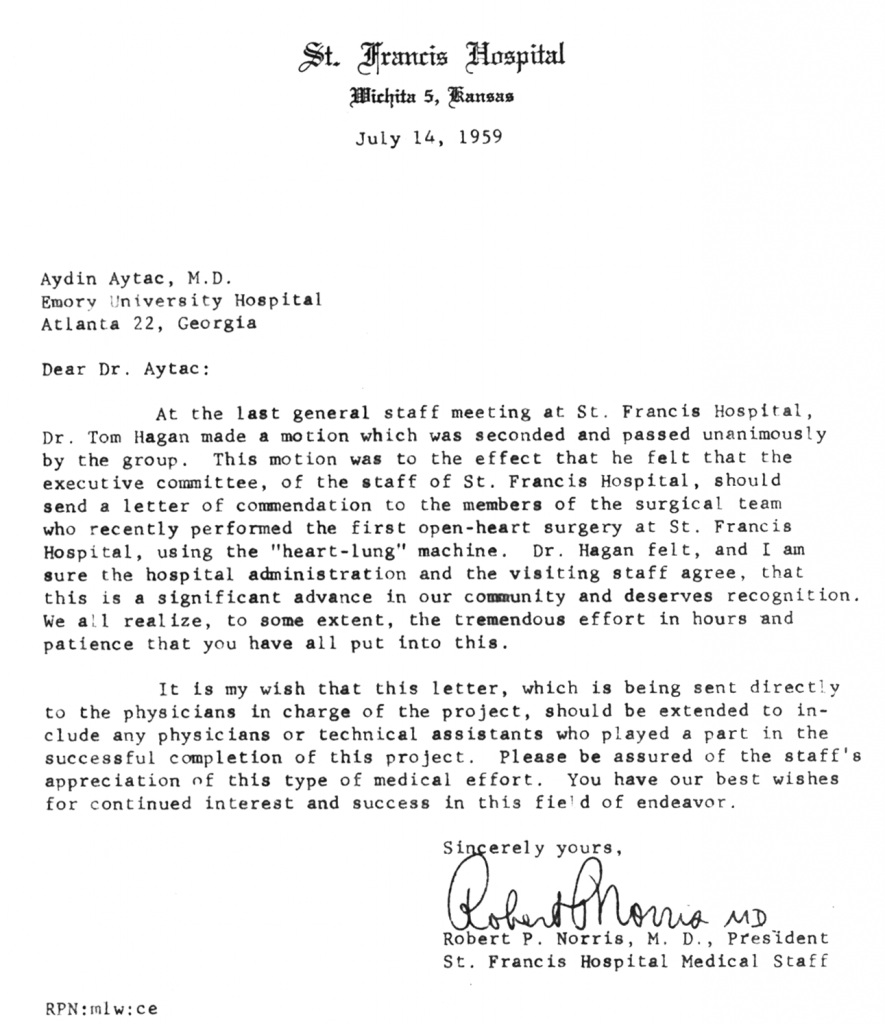

Two days later, on April 23rd, 1959, I started the first heart surgery on a nine-year-old boy, using the artificial heart-lung machine. The cannulation phase and transition to the pump were extremely smooth and easy, and finally I opened the right atrium in the working heart. The blood from the coronary sinus was being aspired and I was looking at the strange sight before me. I was petrified! While I expected a secundum ASD, but what I saw was a septum primum defect. All heart surgeons know how frightening it is to be confronted with a septum primum defect for the first time. The year was 1959. I was only 28 years old and was seeing the inside of a human heart for the first time. In the end, the surgery was concluded successfully. I stayed with the child all through the night and did the necessary checks. In the morning, John Shellito came and examined the child. “God has given us the chance to do this and it was done correctly,” he said. “We have to go on. There is another surgery, and once again, you will do it.” The second surgery was performed on May 26th, 1959, and the patient was released in very good health.

As far as I know, it was the first open heart surgery in the world performed by a Turkish doctor. Hence, I received a formal credit letter from President Robert P. Norris.

(The formal creadit letter sent me by the President Robert P. Norris after the successful open-heart surgery I performed in 1959.)

When I was in the general surgery residency program in the U.S., my father had a stroke and I decided to go back to Turkey. My father was a wonderful person; he wrote me a letter saying, “If you come back before attaining your goal, it will be toughest blow of all for me in addition to the grief caused by my illness. I can’t possibly reconcile myself to the idea of your losing this opportunity because of me. If you complete your residency and continue your program, I promise to make all possible effort to welcome you in the best of health when you return. Please, don’t make me live with this pain; reach your goal first, and then come back.” Many people might say: “I raised you to be a doctor and I want you to come back.” I asked the physician who was taking care of my father, and if he had said there was a risk, I would have returned. He said: “There is no risk, he is an extremely careful person and he has come through it fine.” So I stayed and continued my work and then we lived together for twelve years after my return.

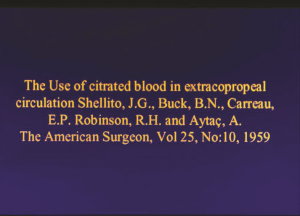

In the article entitled “The use of Citrated Blood in Extracorporeal Circulation,” written by John Shellito and published in The American Surgeon in 1959, my name was mentioned as an assistant along with the general surgeons and the anesthetist in the dog surgery lab. I was proud to be the “first Turkish doctor” mentioned therein.

In the article entitled “The use of Citrated Blood in Extracorporeal Circulation,” written by John Shellito and published in The American Surgeon in 1959, my name was mentioned as an assistant along with the general surgeons and the anesthetist in the dog surgery lab. I was proud to be the “first Turkish doctor” mentioned therein.

←(My name was mentioned in the article by John Shellito published in The American Surgeon.)

(The internship certificate I received upon completing my first year at St. Francis Hospital.)

(The certificate I received upon completing my General Surgery Residency at St. Francis Hospital.)

In my last year, after I finished my presentation as head assistant in the general surgery department, I wanted to go into a formal heart surgery residency program. I applied to a few universities, the best of which was Emory University in Atlanta and they invited me for a two-day interview. There were many applicants and only six candidates were invited. Among those who were invited, two were to be chosen as assistants. You had to stay there for two days for the interviews. I lived far away and could not afford air travel. So I went by bus and I had to change three buses, so it took me 36 hours to get there. I arrived at the university at four o’clock in the afternoon. The head assistant took me to the room where I would be staying and said: “Osler Abbott will do the rounds at 5:00 and he’ll be expecting you to join him.” I said OK, and even though I had not slept properly for two days, I took a shower right away and was more or less awake. I went there five minutes before five.

We went around together for about an hour. “Tomorrow morning at 8 o’clock, I will do a surgery with the artificial heart-lung machine and I’ll be expecting you in the surgery room,” he said. The next day, I watched carefully while he performed the surgery, and as we talked he realized I had quite a lot of experience in this area. After the surgery we talked in his room for more than an hour. It was a very positive conversation in every way. “Aydın, your English is very good, where did you learn it?” he asked. I told him I had learned it in my homeland and I had been speaking it for four years in Wichita. Then he showed me the portrait on his wall. “Do you know the man in this picture?” he asked. “Yes, I do,” I replied. “He’s Evart Ambrose Graham.”  He was very pleased that I recognized his teacher and especially that I articulated his full name, because the middle name usually appeared only as as the initial ‘A’.

He was very pleased that I recognized his teacher and especially that I articulated his full name, because the middle name usually appeared only as as the initial ‘A’.

I have always been very interested in the lives of the great people in the medical world. I had read books about the works and lives of almost all of them. In the book about Graham’s life, there was a one-page picture, the exact copy of the one on the wall, with the full name explicitly written.

(Evart Ambrose Graham (1883-1957))→

Abbot said, “Did you know that Graham was the first surgeon to perform pneumonectomy?” I replied, “Sir, Graham had done pneumonectomy on a patient with cancer in 1933, but the first pneumonectomy was successfully done by Dr. Rudolf Nissen in 1931 on a girl with bronchiectasis.” Abbott looked at me with surprise. “How do you know?” he asked. “Sir, Nissen had worked for six years as Director of the Surgery Clinic at Istanbul University,” I replied.

Abbot said, “Did you know that Graham was the first surgeon to perform pneumonectomy?” I replied, “Sir, Graham had done pneumonectomy on a patient with cancer in 1933, but the first pneumonectomy was successfully done by Dr. Rudolf Nissen in 1931 on a girl with bronchiectasis.” Abbott looked at me with surprise. “How do you know?” he asked. “Sir, Nissen had worked for six years as Director of the Surgery Clinic at Istanbul University,” I replied.

(Rudolf Nissen (1896-1991))→

“When I was a student there, he had left long ago but his name was still alive. I read the life of this great man who had rendered great service to my country. Also, in the well-known surgeon Thorek’s book, it’s written exactly the same as I have said.” As I spoke, I was scanning the books covering the entire wall. I saw the four-volume book there and told him I could show it if he wished. He said, “Go ahead,” and I opened the book. After a little searching I found the section about Nissen’s pneumonectomy in 1931 and I showed it. Abbott honored me by saying, “You wanted to come here to learn, but you’ve taught us something even before you came.”

Later, he said: “You don’t have to stay here for two days since you have extensive experience in heart surgery, so you can leave if you wish. I definitely want you here as an assistant, but I can’t do it right now, because there are two other candidates we haven’t yet interviewed. It won’t be appropriate if we take someone before they arrive, so I’ll send you a telegram a week later.”

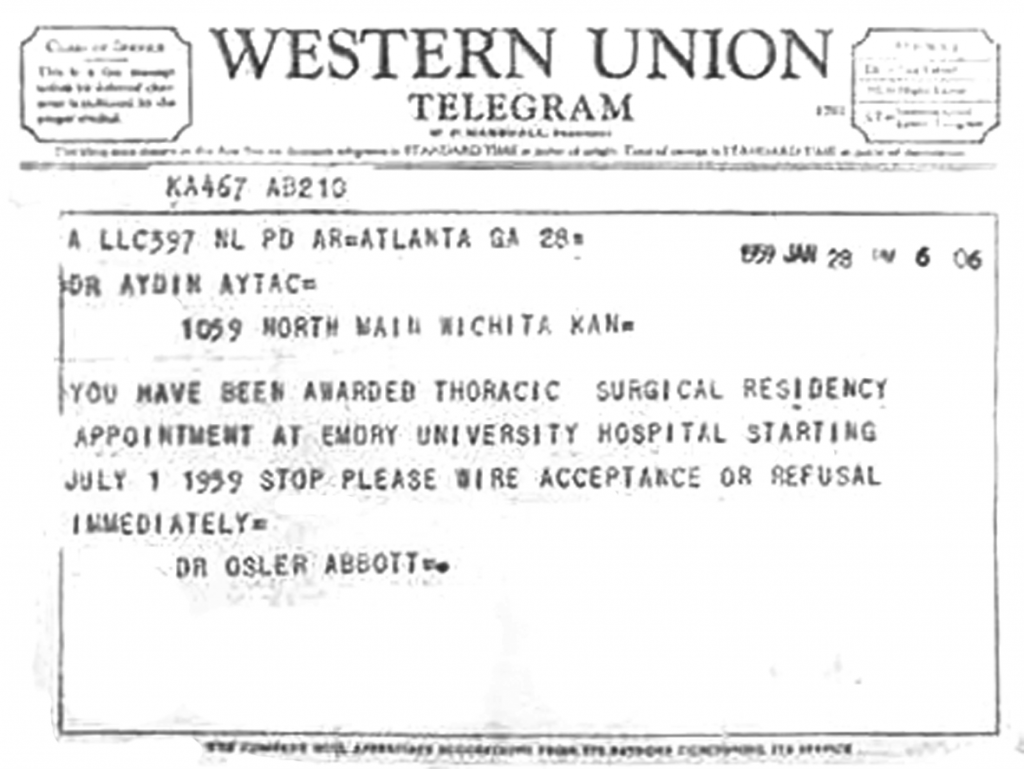

A week after this meeting, he informed me by telegram that I was accepted.

(The telegram from Dr. Osler Abbott notifying me that I have been accepted to Emory University.)

Here I would also like to mention a commendable act of Dr. Evart Graham’s. Although the American Medical Association had honored Graham with a credit letter recognizing him as “the surgeon who performed the first pneumonectomy,” Graham said it was Nissen who was entitled to this honor and made sure that the letter was sent to him instead. Graham’s act was no doubt at least as honorable as earning this recognition by performing such a surgery. The act bears an exceptional value for all scientists in terms of the exemplary relations between two great surgeons who have given the gift of cardiothoracic surgery to humanity.

As far as I was concerned, the biggest disadvantage at Emory University was the financial aspect. My salary was only 175 dollars, whereas at St. Francis Hospital, where I had done my general surgery residency, I had started with 300 dollars a month and it had eventually gone up to 410 dollars. I also received better offers from other universities. Chicago offered 750 dollars a month to assistants; however, when I went there for two days, I saw that they did only cardiovascular surgeries there. Since they didn’t do surgeries with the heart-lung machine, I didn’t accept their offer.

Even though the monthly income was only 175 dollars, I chose Emory University, which I believed was the best in the U.S. under the direction of Osler Abbott.

Dr. Buck, who was my teacher where I worked for four years, said: “You must definitely go to Emory,

but you’re married and have two kids, how much more money do you need?” I told him I would need about 100 dollars more. He then said, “I will send you 100 dollars every month as a gift.”

but you’re married and have two kids, how much more money do you need?” I told him I would need about 100 dollars more. He then said, “I will send you 100 dollars every month as a gift.”

←(My daughter Işık Aytaç)

(My son Demir Aytaç)→

I told him I wanted to pay back my debt when I returned to Turkey, but was concerned about the fact that sometimes it was not possible to send dollars abroad. My teacher’s answer came without hesitation. “You won’t return this money,” he said. “Years later when you reach my position, if you find someone -just like we have found you- whom you highly appreciate as a talented person and if you give him the support that I’ve given you, you will have paid your debt.” What a perfect arrangement it was! I thanked him from the bottom of my heart. For two months he sent me the money. After two months, Osler Abbott won a big fund for the continuation of his research on “The Surgical Cure of Emphysema” and received a total of about two hundred thousand dollars from the National Institute of Health. As compensation for our work in this research, he paid each assistant an additional 100 dollars per month. I called Dr. Buck to give him the news and to tell him I no longer needed his support. He had helped me for two months yet, but he would no doubt have kept his promise and continue to offer his support until the end of my residency. Even though there was no need any more, I knew that I’d been able to go to Emory with the help of his promise and sacrifice, and I never forgot it. Years later, I had the great pleasure and privilege of entertaining Dr. Buck and his wife as my guests in my country.

(Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, where I completed the Cardiac Surgery Residency Program.)

At Emory University, I participated in the surgeries on dogs which were performed once a week under the direction of Osler Abbott.

Other surgeries were performed, also under his direction, on other days of the week: surgeries with an artificial heart-lung machine, as well as other heart and lung surgeries which could be done without a machine. The experience held great value for me and I was very pleased to have found this opportunity. We were performing both adult and child surgeries. The surgeries on children were done in a second pediatric hospital in the same medical complex.

a second pediatric hospital in the same medical complex.

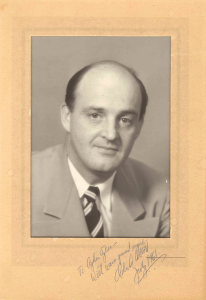

←(Osler Abbott’s photograph which he signed for me.)

(We are at one of the dog surgeries we performed once a week at Emory University under the direction Dr. Osler Abbott. I am the one at the right.)→

One night, when I was on night watch in the intensive care unit, I was summoned to the children’s hospital. The child, whose condition was worsening, had been previously diagnosed and he was to have a lung surgery the next day. When I arrived at his side, he was almost dying. I immediately called Osler Abbott and told him the child could not wait until the morning; he had to have the operation immediately. Abbott said, “I’m coming right away.” He arrived quickly and we started the surgery at five in the morning. I was assisting him and as he finished his work, he said, “Aydın, you do the closure,” and went out of the surgery room. I was about to finish the closing when the anesthetist said, “We cannot feed air into the lungs.” Osler Abbott was immediately called back, but the child was going to die within the few minutes before he arrived. So I made an opening in the trachea, we connected the anesthetist’s air pipe there and the child was immediately relieved. At that moment Osler Abbott came back, all burdened with worry. When he saw the child’s condition, he took a deep breath and thanked me.

At Emory we used to work for long hours and keep a night watch every other day during the first year.

The prime volume of the pumps used in the initial years was quite large, which meant there was need for a lot of blood. Since the heart was opened while it was working, aeroembolism was always a mortal risk. Sometimes unexpected things happened in the surgery room and we were at a loss. One day, when Abbott had opened a heart for VSD (ventricular septal defect), the latex pipe of the pump burst open and most of the blood in the pump spilled out. There was no volume left for extracorporeal circulation. There was air in the tubes and Abbott, in the noisy chaos that ensured, was trying to fill the heart and the tubes with serum. He asked us to collect the spilled blood with compresses and squeeze it into the pump. We were petrified, but since there was no more blood left, we had no other alternative. While we were trying to fill this no-longer-sterile blood into the pump, Abbott finished the repair and quickly closed the heart. By that time the latex pipe was changed and the pump had started to function normally. The patient recovered and although we waited in fearful anticipation, there was no serious infection.

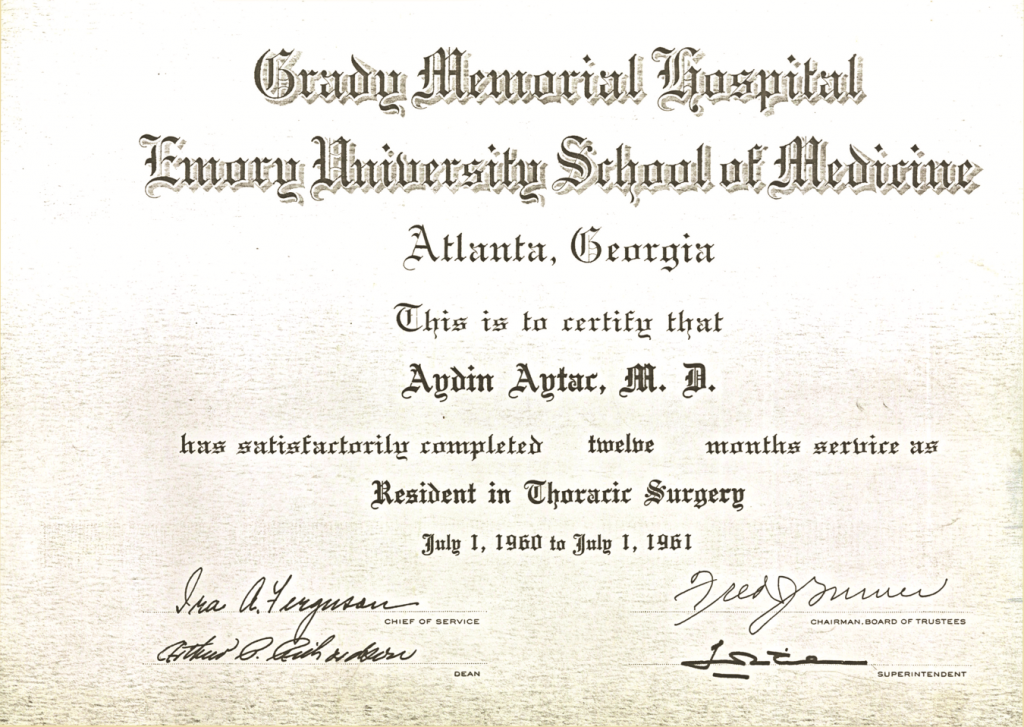

When I was doing my residency at Emory University, I had the opportunity to work for a year in another hospital under a program designed to help assistants gain experience in their last year. In Atlanta, there was a newly built 20-story hospital called Grady Hospital, which was affiliated with Emory University. Highly distinguished professors like J.Wills. Hurst and Ira A.Ferguson were the heads of Cardiology and Surgery departments, respectively. The most remarkable characteristic of this hospital was the fact that all the surgeries were performed by the most senior assistant or head assistant, and the professors did not do any operations, unless it was absolutely necessary. When I said I wanted to participate in this program as head assistant, Osler Abbott told me that he too wanted me to participate, but that so far he hadn’t seen any non-American accepted in the program. He said he would discuss the matter with government authorities, taking advantage of his position in the Department of Health. After a while, I was informed that my application was approved. As a Turkish citizen, I was the only one accepted among the 179 applicants, the rest of whom were Americans.

Since it was my last year, my wife and children returned to Turkey and I moved into a flat consisting of a bedroom and a living room on the twentieth floor of Grady Hospital. Usually I was in the hospital 24 hours a day. I was given a pager with which I could go up to 30 miles away from the hospital. In case of an emergency, I would return immediately.

At this time, hospital assistants were still segregated into four groups: Black women, black men, white women, and white men. There was a person in charge of each group and these group leaders reported to me. Every morning we started the rounds at 7:00 a.m. Every Saturday morning at 7:00 a.m., there was a “death conference”. Each death that occurred during the week would be presented by the assistant, then the head assistant in charge would put forth his defense and the professors would ask questions to locate any mistakes and discuss them. These death conferences were extremely instructive and useful.

The hospital was located in a mostly black area of the city. When the residents of the neighborhood received their weekly or biweekly wages, they would go out Friday evenings to have some fun. We would be especially busy on these days, because there would often be shootings and woundings.

On one of those days a black man with a bullet wound was rushed to the emergency room. When they brought him in, his blood pressure was zero. I had him taken to the surgery room right away. The bullet had pierced through his heart and made a hole on each side. I closed the two holes with my hand and I did all that had to be done. Twenty units of blood were given to the patient. After this case, I told the other assistants about my working principle, which would be the principle of the hospital from that day on: “Anyone who comes here before he’s dead shall not be in any way left to die.”

Another time a wounded man was brought to the emergency room. His wife had wounded him on the neck with a knife. The emergency room was on the ground floor and when they called me I said, “Take him up to the 3rd floor, I’m coming right away.” As soon as I got there, I took him into the surgery room, as his condition was critical. Apparently his wife had killed her ex-husband as well. When I asked him what he would do after he recovered, he answered that he would go home. Then I said: “We may not be able to save you next time. I’ll notify the director and you won’t go home.”

Once, a 73-year-old man with lung cancer came in. I told him he had to have immediate surgery. “Whatever you deem necessary,” he said. When he rose to leave, I said, “Sit down please, I’d like to ask you something. I speak English, but you have probably noticed that I’m not American. I’m only 30 years old, that is, I’m young, too. This surgery is a critical one. How come you didn’t hesitate at all before you consented to my doing the surgery?” He replied, “Yes, your English is good and your accent tells me you’re not American. But I have no hesitation. If you’ve been brought to this position in this hospital, you must be good enough.” I was very pleased, but it saddened me to think that this awareness and trust did not yet exist in my country.

In the period when I worked at Grady Hospital, Pediatric Cardiologist Catherine Edwards brought me a nine year old child with ASD. “He has to have heart surgery,” she said, “but without a machine. In other words, I can’t stop the heart for more than four-and-a-half to five minutes; otherwise I will lose the patient. You have the know-how and the experience, can you do this surgery?” I said I would, but I did not tell Osler Abbott who used to come to the hospital once a week. We would notify him when there was something important.

It was the sixth year of my residency and I had a head assistant who was in his fifth year. I had never seen a case where this technique was used. It was used in a couple of hospitals in the U.S. for cases of isolated valvular pulmonary stenosis, because it was easier and faster. ASD was a more time consuming operation. You had to work very fast and be very well organized. I squeezed the top of the right heart, opened the top and put in the stitches. At the time of closure I held the arteries and opened the inside, then stitched it up completely and closed the heart at the fourth minute. When I was closing the chest, the heart was working fine. Dr. Edwards, who had brought me the patient, also watched the surgery and thanked me profusely. Afterwards, as an expression of her gratitude, she gave me a beautiful picture by an American painter as a gift.

The next day Osler Abbott called me to his office. His face was sullen, but not harsh. “Aydın,” he said, “I heard that you’ve done this surgery. It was a highly critical case. None of us have yet performed a surgery using this technique. What you did was not right, but success covers up all faults.” His words were a warning, intended to make me act with more caution in the future. I believe I gained three or four years of experience there in a period of one year.

Years later, I read in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery the life story of Dr. Samson, one of the most important surgeons of the West Coast. I saw there, under the title, “His Contributions to Medicine in California,” how much importance was attached to the case of ASD closure with inflow occlusion and hypothermia in 1959. It was exactly the same as the surgery I had performed, and only then was I frightened by the magnitude of what I had done. That case was recognized as one of the most important steps on the entire West Coast as well as in the life of a giant heart surgeon in whose name the respected “Samson Thoracic Society” was established. I had dared to do the same thing at the age of 29, about the same time or a year later, partly with the overconfidence prompted by my youth. What if something had gone wrong! It terrifies me even now to imagine it.

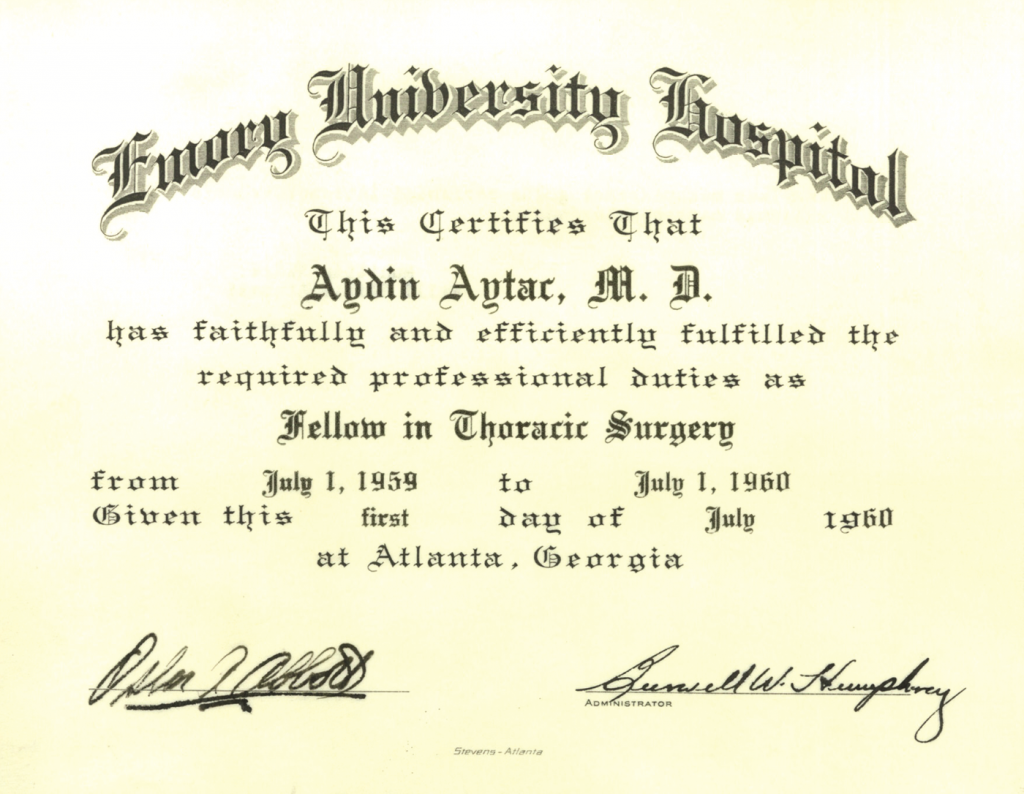

(My Cardiac Surgery Residency certificate from Emory University.)

(My Cardiac Surgery Residency certificate from Grady Hospital affiliated with Emory University.)

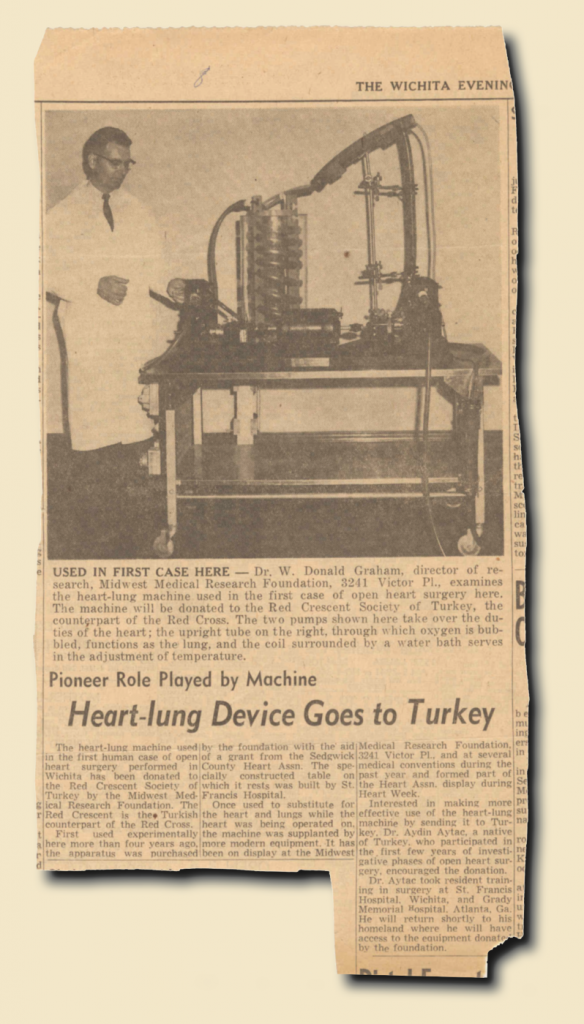

After I completed my formal heart surgery residency at Emory University, I went to Wichita for a week upon an invitation from John Shellito. “Aydın,” he said, “having performed many successful as well as some ‘first-ever’ surgeries, you are now going to Turkey, where these surgeries have never been performed. The Midwest Medical Research Foundation would like to give you an artificial heart-lung machine as a gift and we will send it to your country.” I felt honored and moved by this meaningful gesture.

(The news about the artifical heart-lung machine given to me as a gift by the Midwest Medical Research Foundation when I was returning to Turkey.)

![]()

I had finished my education with the highest honors and reached the stage of making a decision. Where would I continue my professional life? In the U.S. which offered immense opportunities and high standards of life, or in Turkey, my homeland, which was in need of knowledge and service? I’d reached the goal I had set out for and attained an adequate level of professional competence. I returned to Turkey without delay.

When I arrived in Ankara, my wife Şükran, who had come back before I did, told me that Professor İhsan Doğramacı, Founder and Director of Hacettepe Hospital, had called her and said, “When your husband returns, please tell him to come and see me before he contacts any other hospital.”

“All right,” I said. “Ankara Faculty of Medicine is in Cebeci and Hacettepe is on my way, so I can drop by for five minutes and see Professor Doğramacı.”

I had heard the name İhsan Doğramacı, but had not met him before. I dropped by at 9:00 in the morning and could not leave until 5:00 in the evening. “I want you here,” he insisted. “I have collected information about you. You cannot easily practice elsewhere all that you have learned. Here, nobody will interfere with your work; you will have complete control.” I wasn’t sure whether it was me he wanted, or the machine given to me as a gift, and of course I couldn’t ask directly. I had to ask such a question that he would not understand the reason why I asked it, but I would understand the reason why he wanted me. “Sir,” I said. “You have convinced me. I accept your offer, but I have a condition. I promised the Faculty of Medicine at Ankara University, I must give them the machine given to me as a gift.”

Here’s what I thought: If he said, “Aydın, wherever you go, the machine given to you goes with you,” then I would say, “Sorry, I have to go.” But he did not hesitate a moment: “Send the machine to them immediately.  I shall order an even better one for you from the U.S.”

I shall order an even better one for you from the U.S.”

(İhsan Doğramacı, M.D. (1915-2010))→

Professor Doğramacı was an extremely intelligent man. He established Hacettepe University and put a lot of effort in it. The greatest service Professor Doğramacı rendered for the Turkish medicine was to create a favorable environment, as well as an opportunity for young, well-educated doctors to practice in Turkey all that they have learned abroad. If it weren’t for this special environment and opportunities, many young scientists would be demoralized and go back to where they came from so they could continue their work.

On Jan 3, 1962, I accepted Professor Doğramacı’s offer and started working in Hacettepe University Hospital. Until the month of April, I performed five heart surgeries without a machine. It was possible to do so such operations in two types of disease. Thus, we had started a series of open heart surgeries. I presented these cases in June 1962, at the National Congress of Turkish Medicine.

In 1960, Dr. Mehmet Tekdoğan had performed one surgery without a machine at Hacettepe, and in 1961-62, Prof. Nihat Dorken had performed four such surgeries. I did five surgeries in the first month of 1962 in Ankara. All five patients survived and were released from the hospital in good health. Then, within one year, I performed 18 ASD and Pulmonary synthesis operations and all of the patients survived.

had performed four such surgeries. I did five surgeries in the first month of 1962 in Ankara. All five patients survived and were released from the hospital in good health. Then, within one year, I performed 18 ASD and Pulmonary synthesis operations and all of the patients survived.

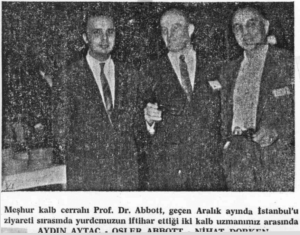

←(The newspaper photograph taken at the time of Professor Abbott’s visit to Turkey. Myself, Osler Abbott, Nihat Dorken)

In April 1963 at the National Congress of Tuberculosis and Thorax in Bursa, I presented the first paper in Turkey about open heart surgeries with extracorporeal circulation.

During my years at Hacettepe, we performed numerous surgeries for the first time in Turkey. In 1962, a male patient was brought to the hospital. He was the father of a lieutenant and was about to lose his life. The only way to save this 66 year old man was urgent surgery to implant a pacemaker. Such an operation had never been done in Turkey and I decided to do it. They were being done in the U.S. since 1960. There were two cases in Europe, and the one at Hacettepe was the third.

I made an international call to Chardack Company. “We urgently need a pacemaker,” I said. “We can’t pay you right now, but rest assured that the payment will be made later.” The man listened to me carefully and said: “It will be at your airport within 36 hours.  You can take it from Pan American.” When the pacemaker came, I said to the customs authorities, “It’s something that will save a human life. Give it to me now and whatever you want to do, do it later.” After a struggle for about four hours, we succeeded in getting our hands on it.

You can take it from Pan American.” When the pacemaker came, I said to the customs authorities, “It’s something that will save a human life. Give it to me now and whatever you want to do, do it later.” After a struggle for about four hours, we succeeded in getting our hands on it.

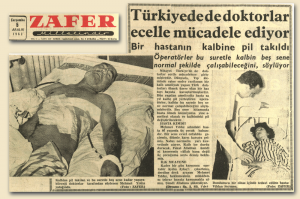

(The news about our first pacemaker implant in Turkey(“Saved from death, thanks to a pacemaker”), Hürriyet Newspaper dated December 6, 1962)→

←(Another news item about the same subject (“Doctors in Turkey fighting against death”), Zafer Newspaper dated December 5, 1962)

In those days pacemakers were not sterile. When the sterilization was completed, I implanted the pacemaker with a left thoracotomy and our patient was saved.

In those days pacemakers were not sterile. When the sterilization was completed, I implanted the pacemaker with a left thoracotomy and our patient was saved.

This was a first in Turkey. The pacemaker attracted a lot of attention and made it to the first page of all the newspapers.

←(My cute little patient for whom I had made an esophagus from her colon)

Again in 1962, when I was at the hospital one night, a little girl was rushed to the emergency room. While she was playing at home, she had drunk chlorinated water which had totally dissolved her esophagus and she was dying. The emergency room staff couldn’t decide what to do. Knowing I was in the hospital that night, they called me and I went to the emergency room right away to see the child. I had her immediately taken into the surgery room. This wasn’t heart surgery, but being a general surgeon as well, I did not hesitate to take immediate action. To replace the entirely destroyed esophagus, I made a new esophagus using a piece of tissue extracted from her colon. A short while after this interesting operation, we released the six-year-old Nuriye Keleş as a healthy and cheerful child.

Years later, I opened a private office and I was doing operations on Saturdays and Sundays as well. During that period, I did eight more surgeries without an artificial heart-lung machine and all the patients were released in good health. I even performed three different types of heart surgery on a Sunday and all three were released under normal circumstances.

In surgeries performed without the artificial heart-lung machine, if the time of operation exceeds four-and-a-half to five minutes the patient loses his life. Due to this critical time limit, some surgeons get too nervous during surgery. However, this is an operation which has to be well-planned from the start and then performed calmly.

When I started working at Hacettepe, I didn’t know the staff there except one doctor who was not a surgeon. Regardless of this fact, two months after I started working there I had the honor of being elected as head of all surgery departments.

I enjoyed the privilege of performing the first open heart surgeries in Turkey, as well as the first heart operations on children. I also performed four general surgical operations for the first time in Turkey. The first surgery I did using the artificial heart-lung machine took place on June 6th, 1962.

In the first days of June 1962, a gentleman came to see me. He was the owner of a hotel in Ankara. “My son is going to have heart surgery,” he said. “Since it has never been done in Turkey, we were planning to take him to Europe. However, for the past four or five months, I’ve been hearing about the successful surgeries you have performed. If you consent, I’ll bring my son to you.” Upon my positive reply, he brought his son the next day. I looked at his examination results and said, “Your case seems to me a little different from the simple ASD. I will do the surgery with the machine. I have so far done five operations without the machine and all of them were successful, but I will do this with the machine.”

On June 6, we set the machine ready and started the operation. The decision to use the machine turned out to be the right one, because we found a septum primum instead of a simple ASD in the patient’s heart.  The defect was extensive. I stopped the heart for 55 minutes, opened it, and did the necessary corrective repairs.

The defect was extensive. I stopped the heart for 55 minutes, opened it, and did the necessary corrective repairs.

(The artifical heart-lung machine we used in the surgical repair of a septum primum defect on June 6, 1962)→

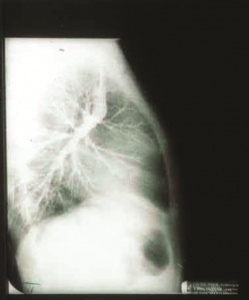

←(The Glenn Operation I performed for the first time in Turkey, 1963)

It was the first such operation in Turkey and we released the patient in good health within a week. Even though I had performed the same surgery in the U.S. three years ago, it was very important for me to do it in Turkey as a Turkish surgeon.

I performed the Glenn Operation for the first time in Turkey in 1963.  As seen in the picture on the left, I cut the blood flow going to the heart and connected it to the right lung and completed the operation by stitching up the part going to the open heart.

As seen in the picture on the left, I cut the blood flow going to the heart and connected it to the right lung and completed the operation by stitching up the part going to the open heart.

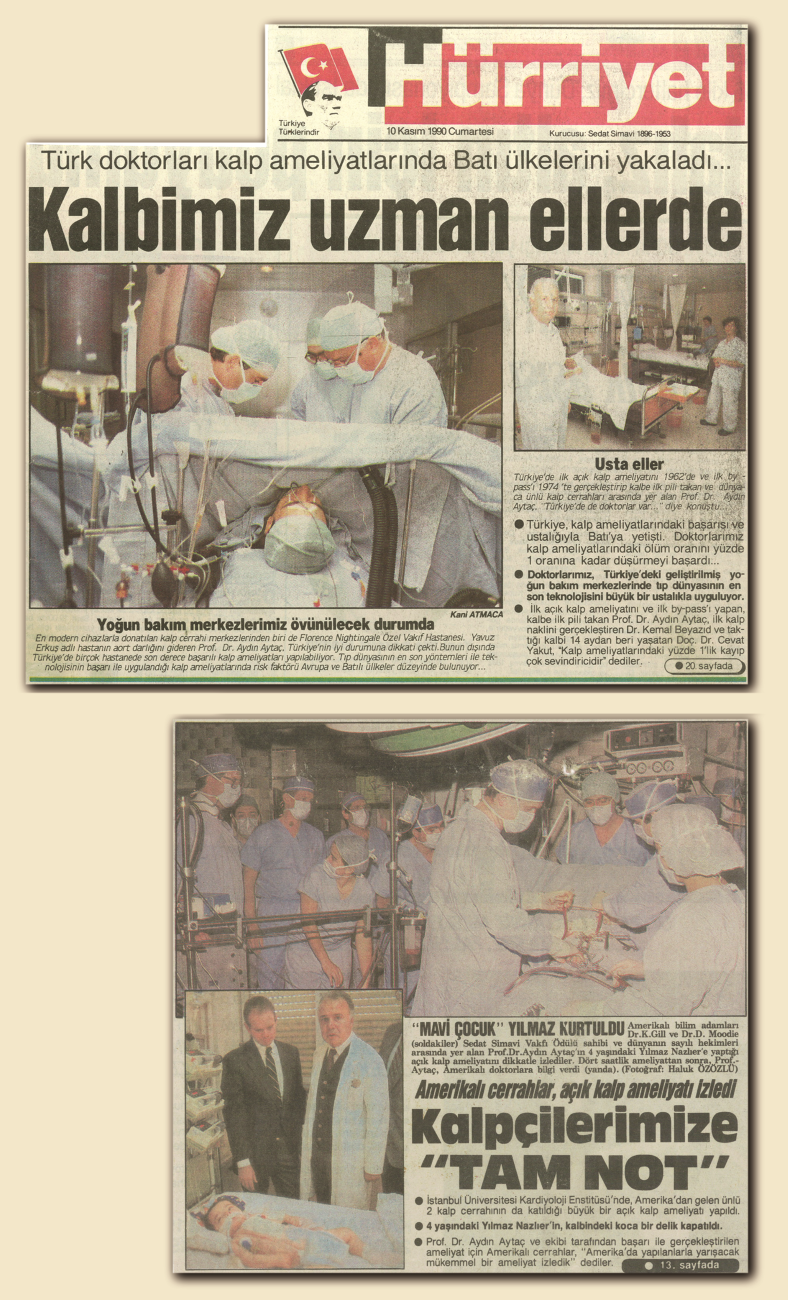

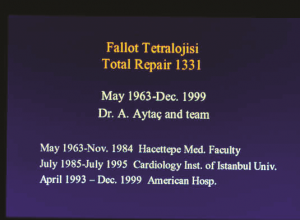

On May 5, 1963 we performed a Total Correction surgery on a youth with Fallot Tetralogy, which was the first such surgery in Turkey. We continued doing Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) surgeries quite intensively during the following years. In 1988, at the first World Congress of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery in Italy, I had the honor of being introduced as one of the four surgeons who had done the highest number of such surgeries in the world.

←(My patient with Tetralogy if Fallot after the first Total Correction surgery in Turkey, May 5, 1963)

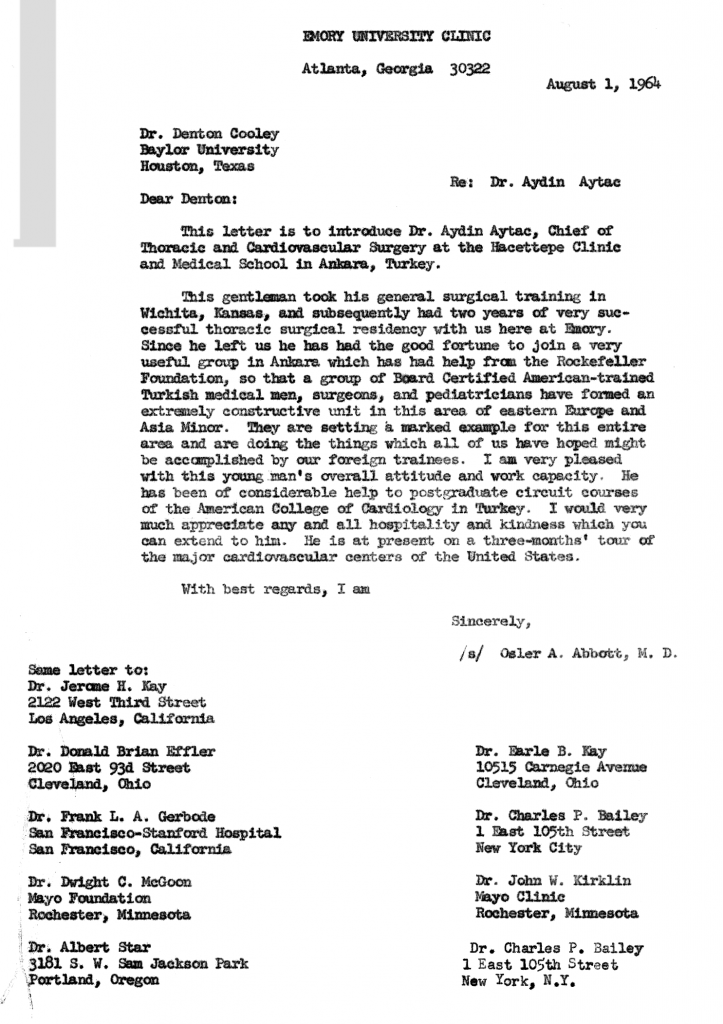

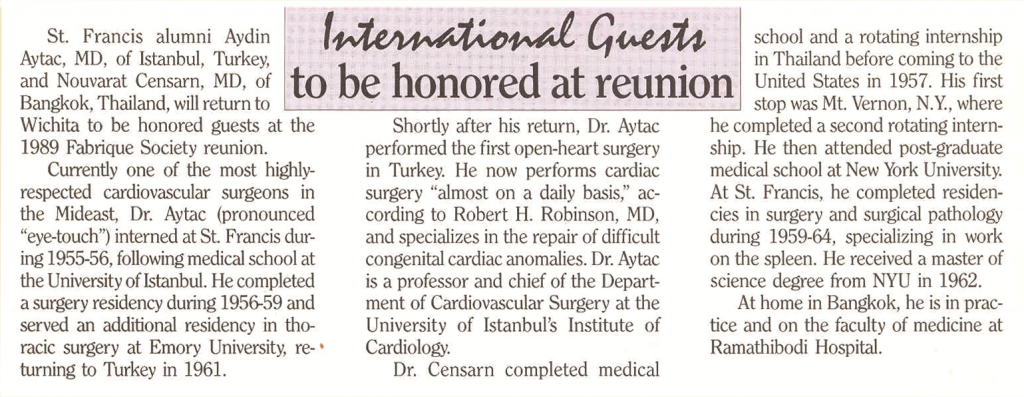

In 1964, I was invited to the U.S. for three months. I was going to visit the top ten surgery centers of the country and stay for a week at each one of them. First I went to Emory University, where I had done my heart surgery residency, and stayed there for three weeks. Then I went to Wichita, where I was moved by the attention I received as the surgeon who had done the “first” surgeries both here and in Turkey. There was news of my visit in the paper, as well as interviews with me on the radio and television.

(The letter of invitation to Wichita, 1964)

(The news in a Wichita paper)

In 1965, Dr. Tahsin Tuncalı, a child internist, sent me a child with the diagnosis of Pulmonary Artery – Left Atrial Defect.

In 1965, Dr. Tahsin Tuncalı, a child internist, sent me a child with the diagnosis of Pulmonary Artery – Left Atrial Defect.  Among the other cases in the world, only three patients had survived. The last case before ours had occurred ten years ago in Germany, but the diagnosis was not accurate and the patient had died six days after the surgery. Ours was the fourth successful operation based on an accurate diagnosis, and the child was completely cured.

Among the other cases in the world, only three patients had survived. The last case before ours had occurred ten years ago in Germany, but the diagnosis was not accurate and the patient had died six days after the surgery. Ours was the fourth successful operation based on an accurate diagnosis, and the child was completely cured.

(My patient after the surgery for Right Pulmonary Artery-Left Atrial Com. Valv. Failure)

With all the wheezing gone, he was released in good health, as seen in the photograph, and he led a normal life thereafter.

Seven years later, a patient underwent surgery in Japan with the same diagnosis and fully recovered his health.

In 1965, I had the honor of earning F.A.C.C. insignia from American College of Cardiology. (Awards-FACC)

In 1969, I set up the first Pediatric Heart Surgery Department at Hacettepe. My book, entitled Cerrahide Şok ve İlgili Problemler (Shock in Surgery and Related Problems), was published the same year.

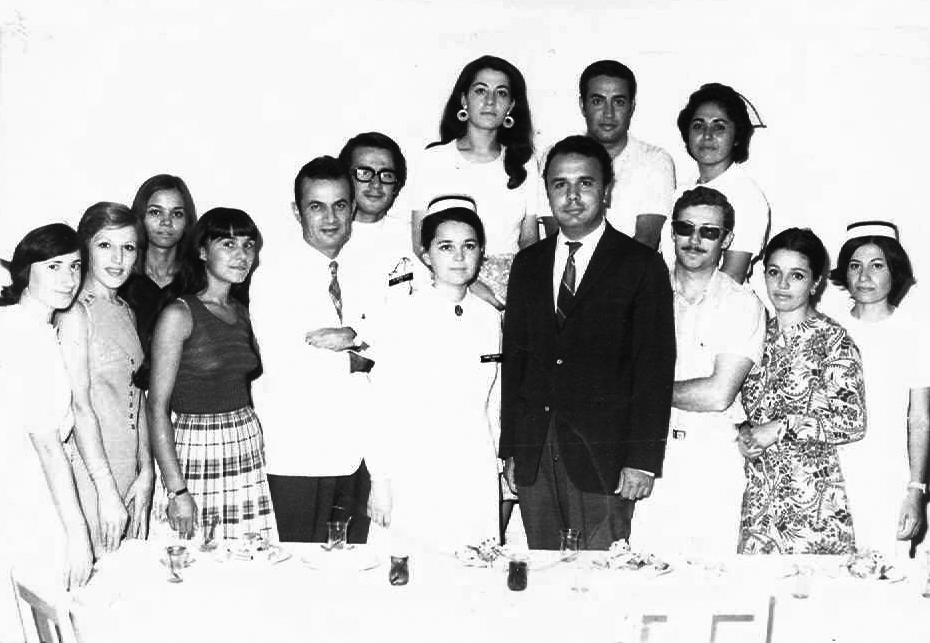

(With my team in the Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Department set up in 1969 at Hacettepe, 1971

Left to right: Nigar Cansönmez, Pervin Öztürk, Suna Aloğlu, Munise Yasin, Yurdakul Yurdakul, Rüstem Olga, Saadet Kalay, Nezahat Akçay, Aydın Aytaç, Günşad Aydın, Coşkun İkizler, Hatice Demirhan, Ayten Yılmaz, Nuriye Yeşilkanat)

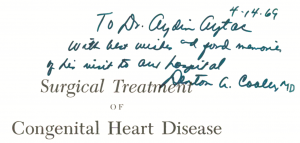

A new book by Dr. Denton A. Cooley, Surgical Treatment of Congenital Heart Disease, also come out in 1969.

A new book by Dr. Denton A. Cooley, Surgical Treatment of Congenital Heart Disease, also come out in 1969.

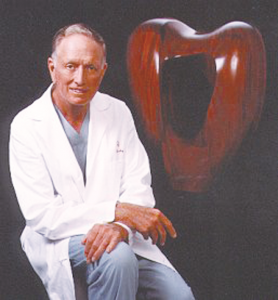

←(The famous heart surgeon Denton A. Cooley and “Symbol Excellence”, the sculpture expressing the artist’s gratitude for the care his daughter received as Cooley’s patient)

the sculpture expressing the artist’s gratitude for the care his daughter received as Cooley’s patient)

(Denton A. Cooley’s book which he signed for me)→

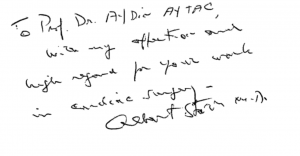

I was in the U.S. for a month that year and I saw Cooley several times. After I watched his operations for a week, Cooley signed his book for me in which he had described the Mustard Surgery. “Before you perform this surgery for the first time,” he said, “read the relevant section in my book one day in advance and let me know about the outcome of the surgery.” In 1970, I did the Mustard surgery in transposition, which I had watched him perform, and I informed Cooley promptly. We continued to perform a series of such surgeries.

I had the honor of earning F.A.C.S. insignia from American College of Surgeons, in 1971. (Awards-FACS)

In 1972, John Shellito sent me a letter saying he wanted to come to Turkey for eight days, together with the surgeons who were on our team in the dog lab for three years: Dr. B. Buck, Dr. E. Carreau, Wichita Clinical Surgery Director Dr. Barlett, and Anesthetist R.H. Robinson, and their wives. “The first two days we would like to visit Ankara and on one of those days we would like to watch your surgeries,” he wrote. “The rest of the time, on condition that your expenses will be on us, we want to invite you and your wife to visit places in Turkey which you might recommend.” I accepted the friendly offer with great pleasure.

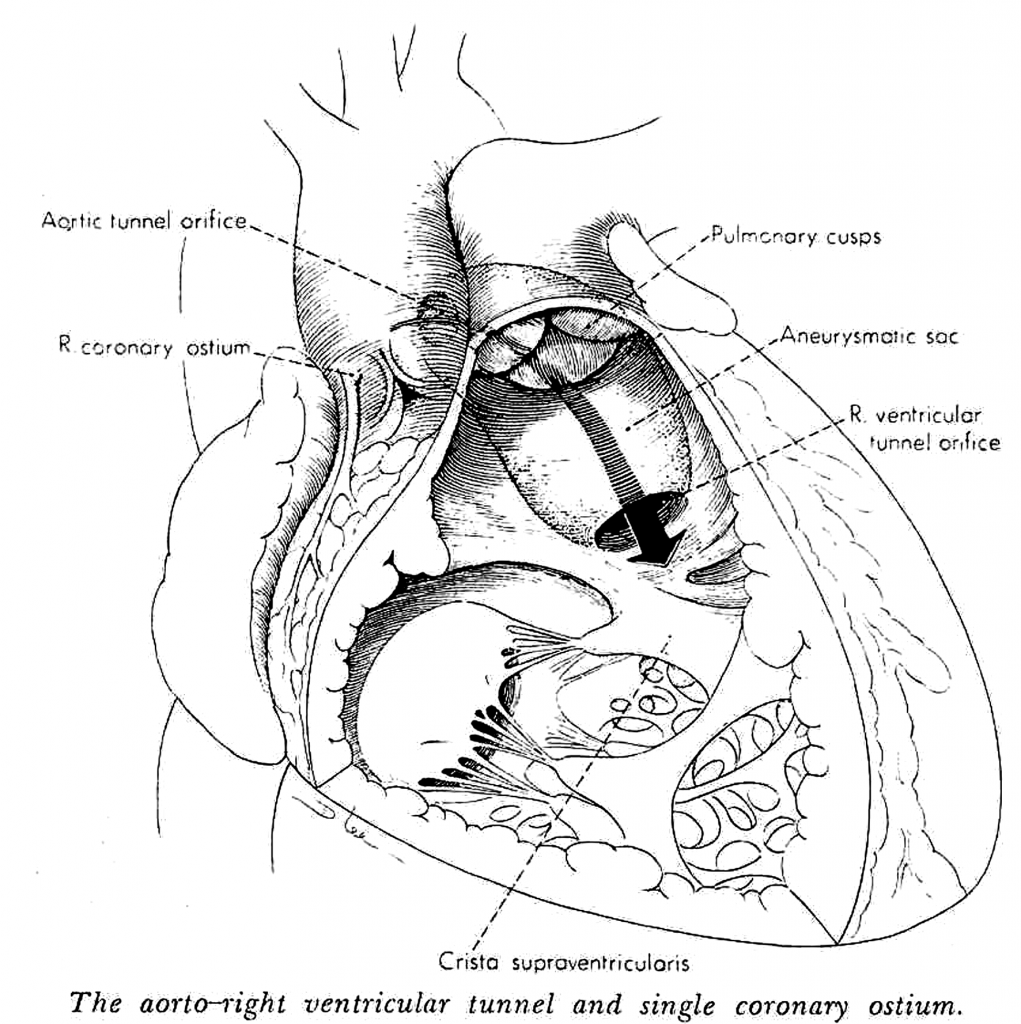

The day after their arrival in Ankara, they watched my surgeries. The first one was a case of Tetralogy of Fallot. After I was finished with the heart, I left it to my head assistant to do the closing and walked into the second room for the surgery involving an aorta-pulmonary window. I opened the pulmonary artery, but unfortunately the diagnosis was not accurate. I opened the aorta and saw that there was no connection between the two. My American colleagues tensed up. “Aydın, here’s a big challenge for you,” they said. I replied, “You just wait for ten minutes, I’ll come up with the right diagnosis.” I found a small hole at the bottom of the aorta and by inserting an instrument inside, I felt a space to the right side of the heart. I opened the stopped heart and found a tunnel between the aorta and the right ventricle. I removed the tunnel and closed the holes in the aorta and the right ventricle. Then I closed the heart and restarted it, and the patient was completely back to normal.

(The operative diagram drawn by Medical Arthist to illustrate “the Aorta-Right Ventricular Tunnel” case after the surgery we performed for the first time in the world)

Thus, I had done the first “Aorta-Right Ventricular Tunnel” surgery in the world. Up until then, the left ventricular tunnel operation had been performed seventeen times in the world and we had done three of those. But the surgery for the right side was performed in Turkey, at Hacettepe, for the first time in the world. The same year, our case was published in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, and the big operative picture drawn by the Medical Artist was sent to me as a gift because ours was the first case.

Dr. Shellito who had witnessed the operation said to me, “A surgeon who performs a surgery for the first time in the world would even consent to giving up his arm. Even if he doesn’t perform a single surgery ever again, he will have made a great name for himself.”

Coming out of the surgery room, the American surgeons spoke to the reporters. Afterwards, we attended the lunch organized by our President İhsan Doğramacı. The next day, my surgeon friends visited the two patients and were very pleased with the results. Then, we visited Anıtkabir, Atatürk’s Mausoleum, and went sightseeing in Ankara. During the rest of their stay, we went to İstanbul, Çanakkale and İzmir.

We did the first coronary by-pass surgery in Hacettepe in February 1974. I performed the operation on a 41-year-old woman using a saphenous vein graft and it was a successful case. The same year Siyami Ersek performed a successful bypass operation in İstanbul. Althouht there are questions as to which of us performed this operation, in part due to the insufficiency of university archives, I think what matters the most is that the two colleagues, unaware of each other’s work, separately introduced a new method of treatment for the good of our people.

After we had returned to Turkey in 1961, I had gone to the U.S. quite frequently on various occasions, but my wife Şükran had never had a chance to accompany me. Our daughter, Işık, and son, Demir, were born there and came back to Turkey when they were very young.

In 1974, we decided to go to the U.S. all together as a family for six weeks. As we were getting ready for our trip, about a fortnight before our departure, I received a letter from Japan. They had a tradition of inviting a successful heart surgeon from outside of Japan as a guest speaker every year and asking him to deliver a 45-minute keynote speech before the graduating students received their diplomas. That year I had the honor of being invited as a guest speaker. As we were getting ready for our trip to the U.S., I wanted to consult İhsan Doğramacı about the invitation. He listened attentively and said, “Send your wife and children to the U.S., but you must definitely go to Japan. It will be a great honor for both Turkey and our hospital. After your visit to Japan, you can go to the U.S. and join your family.”

When I arrived in Japan, the surgeon who had sent me the invitation met me at the airport. I had two suitcases with me, one big the other one small. My host, about ten years my senior, attempted to take the bigger suitcase from me and I said, “Sir, you may carry the small one if you wish, but I’ll carry the big one.” He replied, “No sir, I am your host, I will certainly carry the big one.” It was my first observation of the similarity between Turkish and Japanese people regarding such traditions and behavior.

When I completed my program and delivered TOF speech to the graduating class, I got ready to leave. However, I then received an invitation from another medical school about 300 miles from Tokyo. They were asking me whether I could visit them for two days and give a speech there as well. I accepted their invitation and the day after the conference, I moved on to the other university. There, on the table in the room where I was going to give my speech, I saw about ten or twelve papers written in Japanese, with my name on every one of them. When I asked them what they were, they replied, “You have published many papers in the U.S. and Europe. We have selected these and had them translated into Japanese.” I was impressed by this effort to enable the students to read these papers in their own language.

After the conference, I was supposed to fly back to Tokyo, but they suggested that I go by train. “I already bought my plane ticket,” I said. They told me the airport was rather far and they added: “You cannot enjoy the view if you go by plane. The train ride takes two hours and you can look around and see the surroundings.” Those days the train traveled at a speed of about 170 miles per hour, now it’s much faster. Finally I changed my mind and decided to take the train. They had reserved a special, spacious compartment for me. The front side was entirely open to the view and was so comfortable you could also write and work as you pleased. At that high speed, it ran a little higher above the ground, so you could travel smoothly without the least bit of jolting and discomfort. In two hours I was in Tokyo. Two days later, I flew to the U.S. and joined my wife and children there.

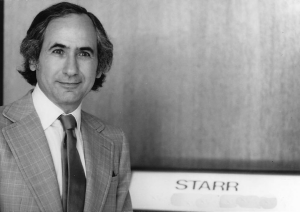

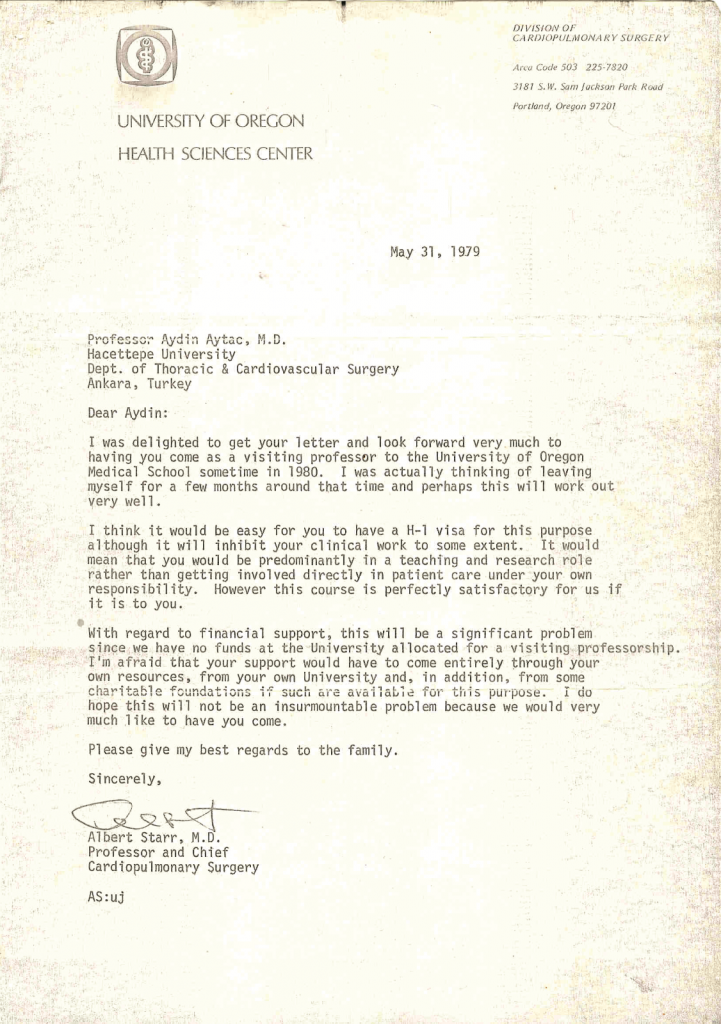

In 1960, Dr. Albert Starr had achieved long-term success in mitral valve replacement for the first time in the U.S..

In 1960, Dr. Albert Starr had achieved long-term success in mitral valve replacement for the first time in the U.S..

←(Albert Starr, M.D.)

I visited him in Oregon and watched his surgeries for three days there. When our work was over, he said, “Aydın, the weekend is ahead. I have a summer cottage 170 miles from here. Let’s take our wives along and stay there for two nights.”  I accepted his invitation with pleasure and we drove there. On the first day we did some horseback riding and enjoyed the surroundings.

I accepted his invitation with pleasure and we drove there. On the first day we did some horseback riding and enjoyed the surroundings.

←(Riding around Albert Starr’s house as his guests. Starr is in the middle)

The next day Albert Starr took me to a place on the lake about 30 or 40 minutes from the summer hut. “Before I perform important surgeries,” he said, “I sit here, take some pebbles in my hand, throw them into the water and watch the ripples and meditate for hours.” In the course of our conversation, he told me it was also here that he had invented the first valve model which began to be widely used in the world. He later showed me those valves as well. For two days, I had warm chats with this very successful man and felt we were like two close friends. At the end of the second day, we returned to the city.

(The letter from Albert Starr inviting me to the University of Oregon in 1979 as he was going to be absent for three months, he had asked me to replace him during that period and suggested that we give the course together during the next three months)

In 1976, Dr. Lillehei came to Ankara for two days. In the afternoon of the first day, he watched a surgery performed by a surgeon friend of mine in a different hospital. My friend later said to me,  “Lillehei constantly intervened while I was doing the surgery, I was under great stress.” In the evening we had a dinner meeting. At dinner there were a few people I had operated on, and we conversed with them as well. Lillehei said, “As you know, tomorrow I will watch your surgery, and in the afternoon I will do a presentation there. Let’s have breakfast together at the hotel tomorrow morning.”

“Lillehei constantly intervened while I was doing the surgery, I was under great stress.” In the evening we had a dinner meeting. At dinner there were a few people I had operated on, and we conversed with them as well. Lillehei said, “As you know, tomorrow I will watch your surgery, and in the afternoon I will do a presentation there. Let’s have breakfast together at the hotel tomorrow morning.”

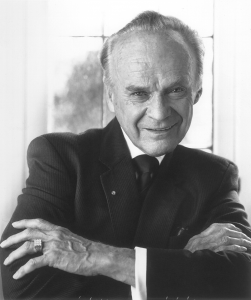

The next day, I went to Lillehei’s hotel and we had breakfast together. He gave me an autographed copy of his newly published book, Congenital Malformations of the Heart.

(C. Walton Lillehei had signed his book for me prior to watching my surgery in Ankara in 1976)→

I thanked him and said, “I wish you’d given me this book yesterday, I could read it last night and draw upon it during today’s surgery.” He comforted me by saying, “You’re one of the most experienced surgeons as far as today’s surgery is concerned. You have done more than three hundred TOF surgeries, so I can only watch you. Any intervention is out of question.” Then we went into the surgery room and we answered the questions posed by the assistants there. After the surgery, Lillehei did a presentation at three in the afternoon. With only seventy-five people invited, he delivered a 45- minute speech at a very special venue. Then he said, “I want you to watch a 10- minute film of the surgery I performed.” Before he started showing the film, he added: “But this morning I watched a surgery better than the one you will see in the film.” It certainly was a flattering compliment from one of the best surgeons in the world regarding the surgery in question.

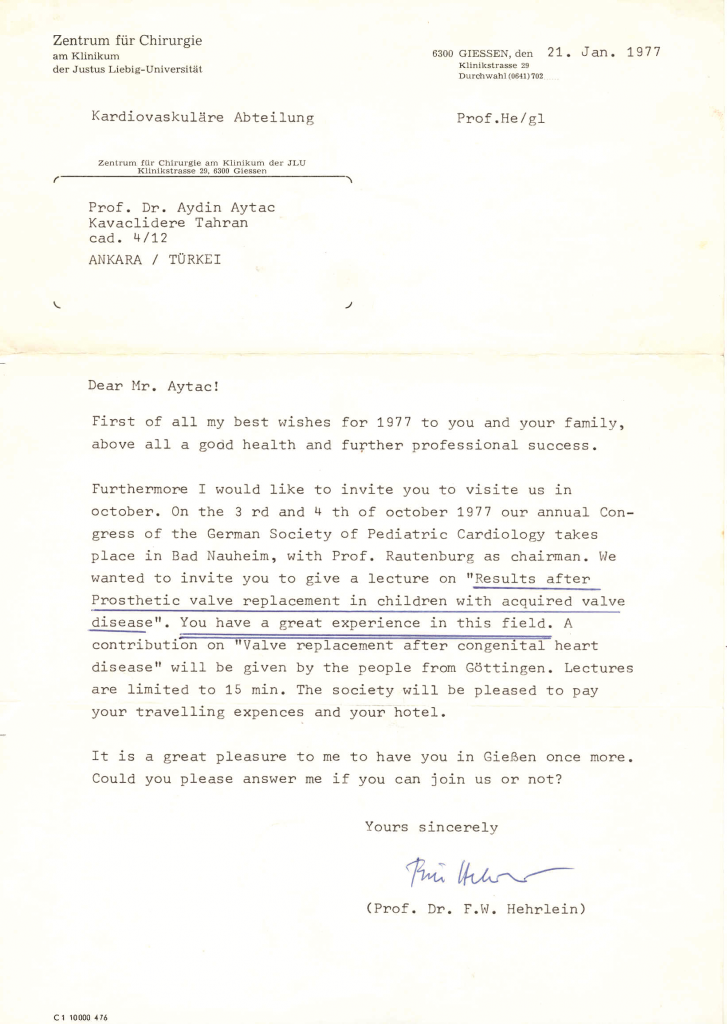

In 1977, at the congress organized by the German Society of Pediatric Cardiology, I presented a paper entitled, “Results after Prosthetic Valve Replacement in Children with Acquired Valve Disease.”

(The letter from Professor Hehrlein inviting me to give a lecture at the German Society of Pediatric Cardiology Congress)

Fritz Hehrlein, Director of German Society of Pediatric Cardiology, was a very close friend of mine who had also come to Turkey several times. The congress took place outside Germany. Hehrlein had driven there in his car and I had flown in from Turkey.  After the congress he said, “Why don’t we drive together back to my home in Germany? I would like you to be my guest. We can change your ticket and you can fly back to Turkey from Germany.”

After the congress he said, “Why don’t we drive together back to my home in Germany? I would like you to be my guest. We can change your ticket and you can fly back to Turkey from Germany.”

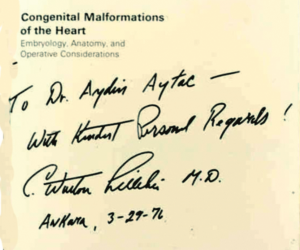

On June 15th, 1978, I was invited to the U.S. by the Wesley Medical Center and did a one-hour presentation on “Prosthetic Valve Replacement in Children with Acquired Valve Disease” once again in Wichita, Kansas.

←(The program for the one-hour lecture I gave on June 15, 1978 in Wichita)

In 1979, I had the honor of receiving the Health Sciences Award given by the Sedat Simavi Foundation. (Awards-SSV)

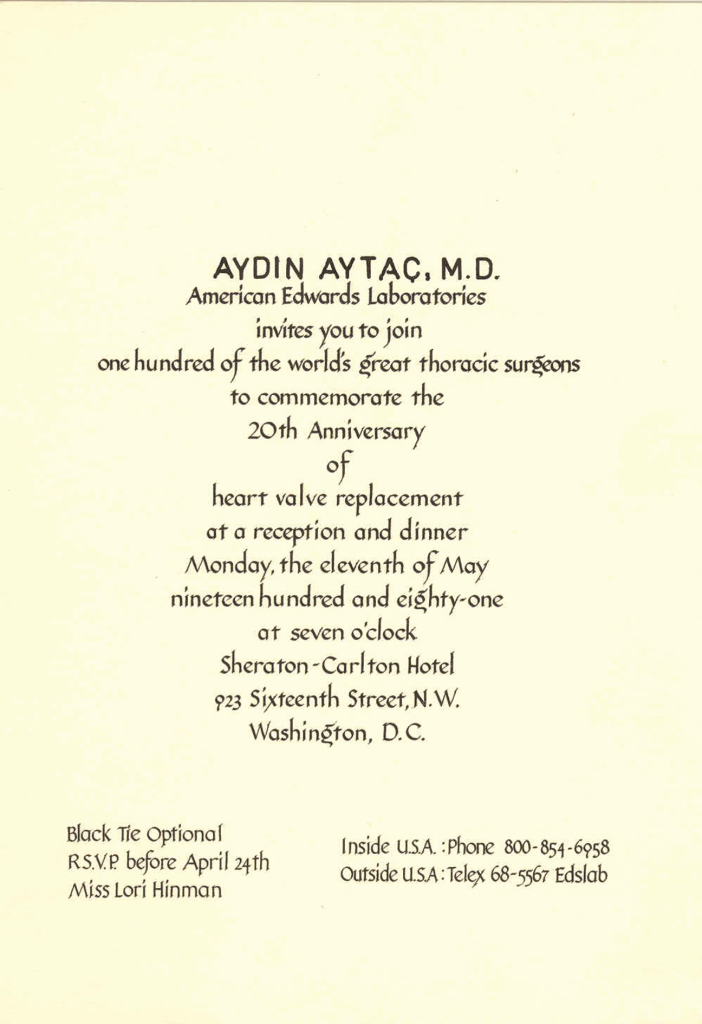

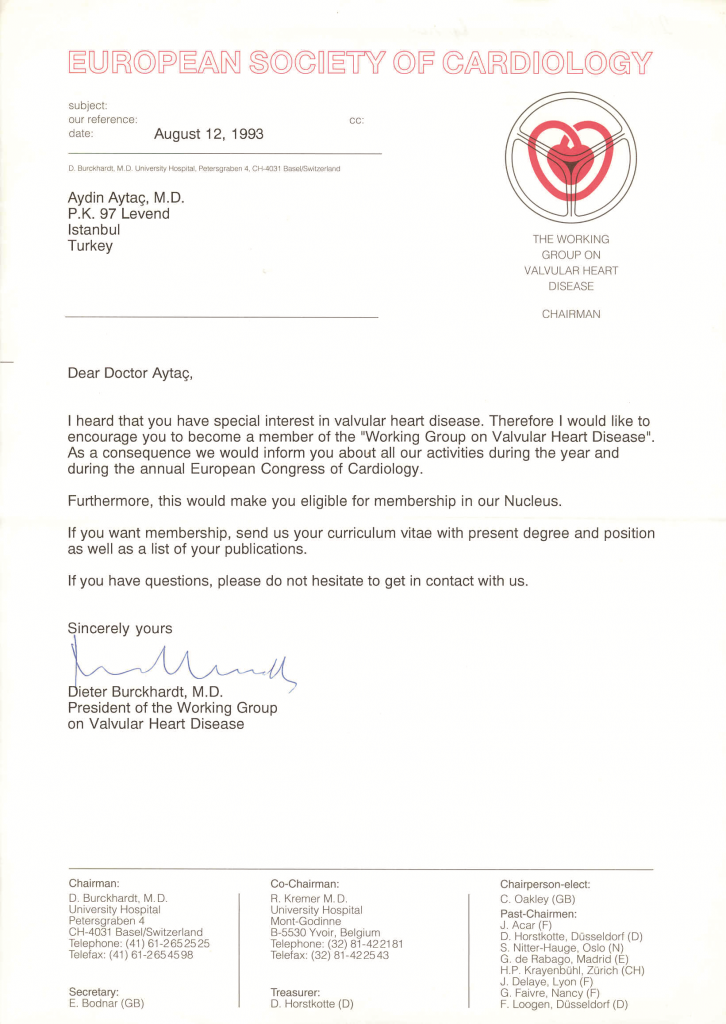

I was invited as one of the “Worlds 100 Great Thoracic Surgeons” to a commemorative event organized by American Edwards Laboratories in 1981

(I was invited as one of the “World’s 100 Great Thoracic Surgeons” to a commemorative event organized by American Edwards Laboratories in 1981)

In the fall of 1984, I acted as chairman of a panel at the Congress of Cardiology organized by the Turkish Cardiology Association. The biggest five hospitals, where surgeries were performed on patients between ages 0-16, using an artificial heart-lung machine, were asked to declare their number of cases. There were 380 people in the audience and the directors of heart surgery units of each of the five hospitals announced their results for the 0-16 age group.

In the end, I turned to them and said: “Your presentations were very good, but I didn’t hear of any cases in the 0-4 age group. Did I miss it? I will ask each of you separately.” When I asked them, they reported that in this age group no surgery had been performed with the artificial heart-lung machine. Then, as the first surgeon to perform surgeries in this group, I was asked to report our figures. Upon my request my head assistant announced the following list of cases in the 0-4 age group: 596 cases in the 0-4 age group and 192 cases in the 0-2 age group. These numbers represented quite impressive statistics promising a better future for young children and babies who needed heart surgery.

At Hacettepe where I had become an associate professor in 1964, I became a full professor in 1969. While I was continuing my work and surgeries in my department, I also served as Dean of the Faculty of Postgraduate Education in 1971-1972, and Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences between 1972 and 1975. In 1984, we moved from Ankara to Istanbul.

![]()

Istanbul University Years

In 1984, I established the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Institute of Cardiology at Istanbul University and worked there for 10 years.

Within this period I also set up the Cardiovascular Surgery Department at Florence Nightingale, a foundation hospital affiliated with Istanbul University, established by the rectorate of the university.

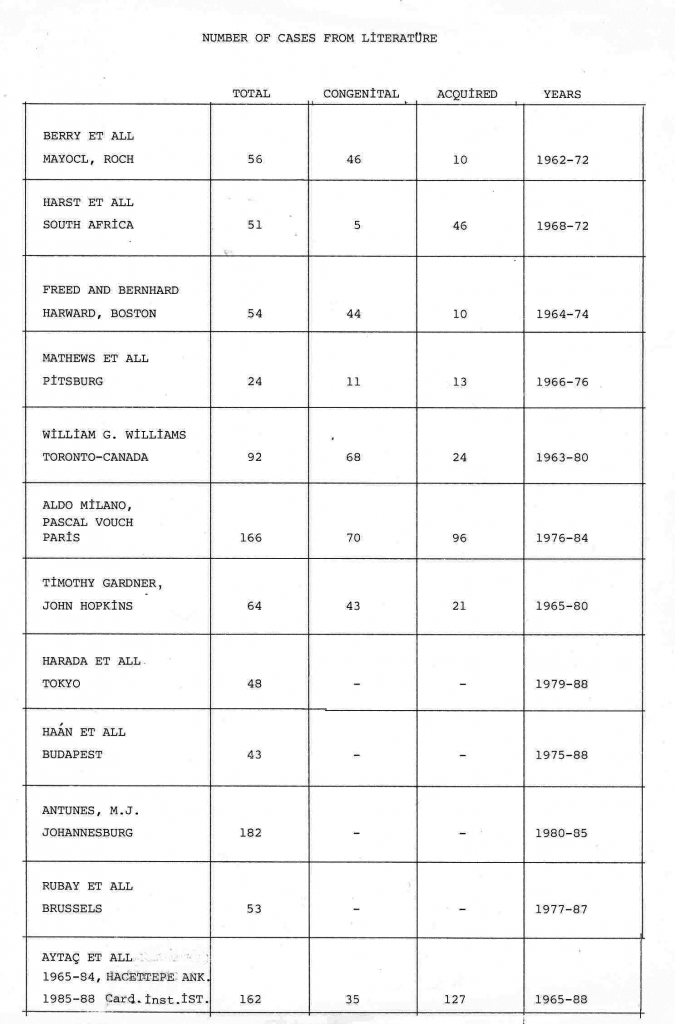

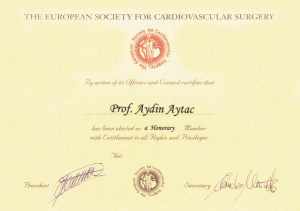

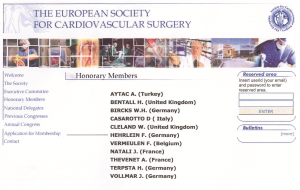

In 1987, at the European Society for Cardiovascular Surgery Congress, I made a speech as one of the first four surgeons who performed the highest number of TOF surgeries. We ranked third with respect to the total number of surgeries, but were the first in the Acquired Series.

(The document showing that we ranked 3rd in the world in terms of total number of surgeries and 1st in the “Acquired” series at the International Congress of The European Society of Cardiovascular Surgery in 1987)

When Dr. John Shellito came to Istanbul in 1988, Professor Cem’i Demiroğlu, President of Istanbul University, asked him to give a lecture at our university and Shellito accepted our request. After the lecture, Cem’i Demiroğlu thanked Shellito and presented him with a plaque.

(Professor John Shellito also showed protographs in the course of his presentation. Seen in the photograph on the screen is the team, including Shellito and me that had started our first dog surgeries in the U.S.

In the photograph below, Professor Shellito is receiving a thank plaque from President Cem’i Demiroğlu after his lecture at İstanbul University.)

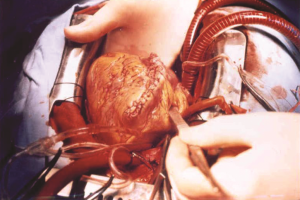

The next day, in order to watch the two surgeries I was going to perform, Shellito came to the university again. Shellito’s wife and my wife Şükran would wait for us in my room, and we would all go out for lunch after the second surgery. Shellito and I went into the surgery room. There were two really big surgeries and Shellito was watching very carefully. We finished the first one and passed on the second. But as you can see in the first photograph, the heart was in unrecognizable condition.

(The congenitaly deformed heart prior to surgical inventation, and then at the final stage of operation)

When Shellito saw it, he said, “You will probably remove this heart and implant another one.” I replied: “I will remove it, repair it, and keep it in its place.” He said it was not a case often encountered in the US; he had done it only once. On the contrary, it was a case I frequently handled. We do not use the artificial heart-lung machine for many of them, but this patient’s heart was in total disrepair all the way inside, so we connected him to the machine. It was a very challenging operation, but at the end the heart was restored to the condition you see in the second photograph. I had also repaired the defects inside the heart.

We had started at 9:00 in the morning and finished at 1:00 PM, and then we went out for lunch with our wives.

In 1988, I had the honor of being awarded as one of the “Ten Golden Scientists of Turkish Medicine” in the “Republican Era Medicine Awards” organized by Eczacıbaşı, a prominent Turkish Industrial group. (Awards-Eczacıbaşı)

The first World Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Congress was held in Italy in 1988. At the congress, the four groups that performed the highest numbers of total correction surgeries, a very important category in pediatric cardiac surgery, were selected for a special meeting. As the leader of the third of these four groups, I was invited to the congress and I presented our case in detail. There was a specific debater for each of us. My debater was Dr. John Kirklin, the famous heart surgeon who had performed the first total correction surgery with the artificial heart-lung machine at Mayo Clinic. He delivered an elegant speech in support of our case.

(John Kirklin (1917-2004)

His book, which he signed for me in 1974)

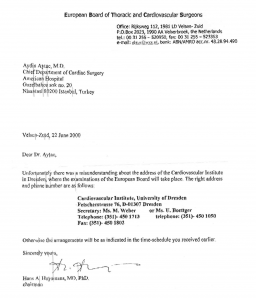

We continued to perform our surgeries at an intense rate and after 1988 we did the operations without cardiac catheterization unless it was imperative to do otherwise. Between 1988 and 1993, we performed 99 surgeries without cardiac catheterization and we lost only two children; the rest survived. In 2002, the number of cases and surgeries went up to 1377 and we presented these at the congress in Helsinki.